On Tuesday, the Knight Institute and the ACLU filed a lawsuit challenging the constitutionality of a far-reaching system of government censorship. The system, known as “prepublication review,” prohibits millions of former public servants from writing and speaking about their government service without the government’s prior approval. The lawsuit contends that the system is unconstitutional because it vests too much discretion in the government’s censors and fails to provide procedural safeguards that the First Amendment requires.

We brought our lawsuit on behalf of five clients, who you can read about here. And over the past several years, we’ve spoken with dozens of former government employees who have told us similar stories about the state of the prepublication review system. But we have also learned a great deal about the failings of that system through the government’s own documents.

The lawsuit is based in part on thousands of documents that the Knight Institute and the ACLU obtained in response to multi-year Freedom of Information Act litigation. We are publishing many of these documents today, and we’ll be publishing more in the coming months.

These documents illustrate many of the fundamental problems with the current prepublication review system.

First, the government’s documents show that the prepublication review system is a tangled mess. We already knew that agencies imposed prepublication review obligations through a patchwork of internal policies, regulations, and contracts. But the documents show us just how fractured and complicated the system really is.

When we filed our first FOIA request in March 2016, many of the documents that explain agencies’ prepublication review policies and processes were publicly available—but surprisingly, many weren’t. After we sued eighteen agencies under FOIA, we were able to uncover several of those hidden documents.

For example, the CIA produced an agency regulation titled “Agency Prepublication Review of Certain Material Prepared for Public Dissemination” that “sets forth CIA policies and procedures for the submission and review of material proposed for publication or public dissemination by current and former employees and contractors and other individuals obligated by the CIA secrecy agreement.” (Previously, the only publicly available version of this document was heavily redacted and more than eleven years old.)

Thanks to the documents we’ve shaken loose we’ve been able to fill in major holes concerning the agencies’ prepublication review regimes. For example, we now understand that the CIA’s regime includes the now-released regulation and at least three nondisclosure agreements—including two that appear to be in use across the intelligence community, and one that all CIA officers must sign as a condition of employment.

The cache of documents also makes clear that the prepublication review system is a bureaucratic morass. Submission and review standards, review timelines, and appeals processes vary widely across the agencies. What’s more, many authors must submit the same manuscript to more than one agency, and agencies conducting prepublication review often refer submissions to other agencies which have their own so-called “equities” in deciding whether to censor the material. As a general matter, this referrals process is almost entirely opaque to authors. Often, authors are not told to which agencies their manuscripts have been referred, and even if they are told, they are most likely not informed what standards these agencies will apply.

Second, the documents we obtained show that authors frequently have difficulty determining what must be submitted, because submission requirements are vague and sweep in a vast range of innocuous material.

An email exchange produced by the FBI is illustrative. In the exchange, a former FBI employee contacted the agency’s prepublication review office about a novel he had written about criminals who rob armored trucks. The story, he said, was “purely fictional.” It was set in 1988, before he had even entered the Bureau, and it took place in Atlanta, a city to which he had never been assigned to work. All of the characters’ names were made up. Though he had investigated armed robberies while working at the FBI twenty-three years prior, he did not include any information he acquired from the FBI in his story. In his view, the draft manuscript didn’t “fit[] within the purview of the pre-publication guidelines,” which require the submission of “knowledge gained through FBI employment or assignments related to the FBI.” But the FBI reviewers disagreed, asserting that the manuscript could still disclose “sensitive techniques or methods.” They told the author to submit.

Remarkably, the documents also show that the CIA at least has deliberately kept submission requirements shrouded. A document produced by the agency states that, as a matter of policy, the CIA’s Publications Review Board “will not provide a copy of a secrecy agreement or nondisclosure agreement to an author who requests one they signed,” even though these agreements “are typically not classified.”

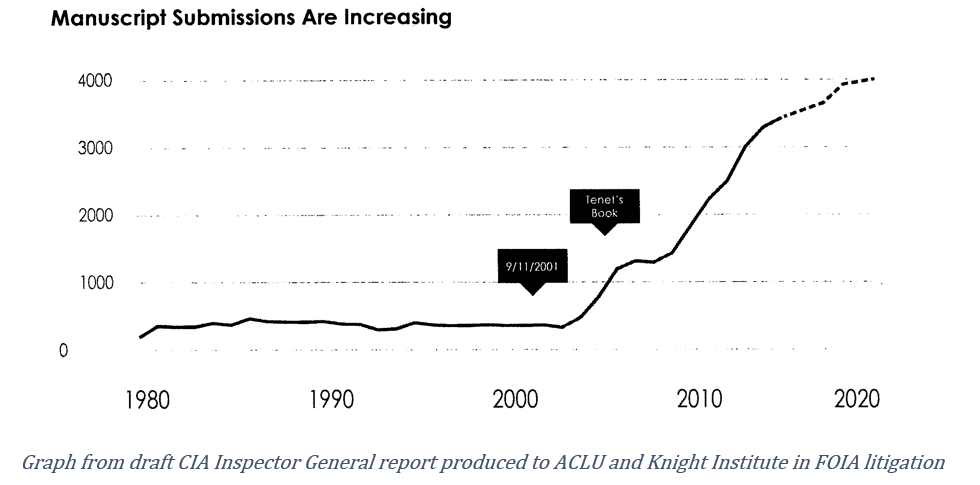

Third, the government’s documents reveal that the system is overwhelmed. The amount of material being submitted for prepublication review has increased dramatically in recent decades. For example, when the CIA’s PRB formally came into existence in the 1970s, it reviewed approximately 1,000 pages per year. In 2014, the board reviewed over 150,000, averaging a rate of 400 per day.

As the number of submissions has increased, so too have the frequency and severity of delays. For example, in 1982, the average PRB review took just 13 days. Today, review takes much longer. According to a draft CIA Inspector General report provided to us, “with today’s volumes, complexity, and strive for immediacy, PRB is struggling with achieving timeliness, and to some extent thoroughness/quality.” The report also states that “book-length manuscripts received today are currently projected to take over a year because of the complexity and large book backlog.”

Charts produced to the ACLU and Knight Institute in FOIA litigation confirm that other agencies have seen similar increases.

Fourth, the documents confirm that favored officials are sometimes afforded special treatment, with their manuscripts fast-tracked or seemingly subjected to less scrutiny. For example, while it took NCIS-veteran Mark Fallon nearly eight months to get his book reviewed, it took former FBI Director James Comey and Secretary of State Hillary Clinton just seven weeks and eight weeks, respectively. In Clinton’s case, agency censors were explicitly warned: “The [review] office is under great pressure to turn this around quickly. If you are tardy in your response, you may get a high-level Department official call.”

We have found no official guidance setting forth factors to determine when an author should receive special treatment. It appears to be personal and arbitrary.

Fifth, the documents demonstrate that administrative appeals processes fail to afford authors effective recourse for erroneous censorship decisions. Delays are one problem. For example, an administrative appeal lodged in 2014 by former intelligence officer Michael Richter appears to have taken over seven months to adjudicate. This, despite the fact that the appeal “require[d] analysis of one sentence, in one paragraph, citing one document”—and the author’s insistence that he had “only learned of [the excised] information by virtue of having access to the New York Times website.”

Another problem is lack of transparency. Because authors who receive adverse prepublication review determinations rarely get an explanation—or at least a meaningful one—they are unable to effectively address censors’ concerns.

To make matters worse, authors are unable to directly appeal redactions mandated by other agencies to those agencies. Take Richter’s case, for example. As a former DIA and ODNI officer, he submitted his manuscript to the Defense Department. The manuscript was subsequently referred to the ODNI and the CIA, and it was the CIA that insisted on the redaction. However, Richter was unable to directly appeal the CIA’s redaction to the CIA. Instead, he was required to lodge an appeal with the Defense Department, which was permitted—though, it seems, not obliged—to ask the CIA to reconsider its decision.

Individually, each of these revelations may offer only a relatively small insight into the pathologies of a sprawling system, but, collectively, they are striking. For years, prominent voices from across a broad spectrum of political ideologies and government work experiences have observed that the prepublication review system is broken. Now, the government’s own documents confirm it.

Ramya Krishnan is a senior staff attorney at the Knight Institute.