I. Introduction

If you purposefully set out to concoct a government policy guaranteed to be unconstitutional, here is how you would do it. You would impose a restraint that forbids people from expressing viewpoints on contested political issues that dissent from the government’s official position. And you would justify the restraint by arguing that, if the citizenry is given the whole truth, they might think less of the government.

This restraint doesn’t exist in the fever dream of a constitutional law professor writing a final exam. It’s real. It’s called a “one board” or “one voice” policy, and it appears to be commonplace at school boards, college trustee boards, and other government policymaking bodies across the United States.

These policies typically provide that members of elected or appointed governing bodies are forbidden from expressing disagreement with the body’s majority position once an issue has been voted on. The rationale for them is simple: to create the impression that the board is united—even if the unanimity is feigned.

To cite just one example, school districts across the Flint, Michigan, area reportedly enforce regulations that forbid elected school board members from “publicly sharing their opinions on any school district issues,” requiring board members to submit any questions they receive to the district superintendent. Similar restrictions have been imposed by elected or appointed governing boards throughout the country.

This article concludes that “one board” rules are indefensible both as a matter of First Amendment law and as a matter of public policy. There is no doctrinal support for the position that attaining government office means forfeiting all free speech rights. The ability to dissent from the government’s official viewpoint is so foundational to the purpose and function of the First Amendment that it cannot be implicitly waived by assuming a governmental position. In particular, gagging board members who are popularly elected, as opposed to appointed, squarely implicates the First Amendment right of their constituents to receive information—information that may be critical in deciding whether to reelect, or replace, sitting officeholders.

This article begins in section II by setting out the boilerplate First Amendment principles that sharply limit the authority of government agencies to restrain speech or to punish speakers for the content of their messages. Section III examines how courts have come to tolerate more speech-restrictive policies in the workplace setting, in deference to the countervailing efficiency concerns of government managers. Section IV inquires whether people in elected or appointed lawmaking positions—positions where speaking to the public is intrinsically a responsibility of the role—have the benefit of full First Amendment protection when they speak or only the diminished level of protection that applies to rank-and-file employees. In light of these principles, section V then examines the phenomenon of the “one board” or “one voice” policy in government service and considers how a constitutional challenge by speakers restricted from expressing dissenting viewpoints might play out. Section VI concludes that, both as a matter of constitutional law and as a matter of sound civic policy, it is intolerable to gag policymaking board members—the government employees whose voices the public most needs to hear—from speaking candidly about why they cast their votes.

II. Free Speech Foundations

In many ways, the heart and soul of the First Amendment is its proscription against what are known as “prior restraints”—government directives that categorically forbid speech. A prior restraint is considered especially offensive to the First Amendment because it prevents the speaker from ever reaching the intended audience, impairing the “marketplace of ideas” that the Constitution fiercely protects. Once a regulation is understood to be a prior restraint, it almost invariably will be deemed unconstitutional, unless it is proven to be necessary “to further a state interest of the highest order.” Not even concern over the impending disclosure of classified information gives the government a free hand to restrain speech. The Supreme Court has indicated that, under extreme circumstances, a prior restraint might be justifiable. But the Court has yet to encounter such a circumstance, even when publishers are accused of disseminating damaging or intimately personal information.

When a government restriction is directed at the content of a speaker’s message, the restriction is presumed to be unconstitutional unless it can surmount strict judicial scrutiny. Satisfying strict scrutiny requires the regulator to demonstrate both that the restraint addresses a compelling public need and that the restraint is the least speech-restrictive means of achieving that purpose. Viewpoint discrimination is an especially odious variation of content discrimination, singling out one side in a contested matter for disfavored treatment. As with prior restraint, once a government action is regarded as viewpoint-discriminatory, it is almost guaranteed to flunk constitutional scrutiny. While viewpoint-based or content-based regulations are always regarded skeptically, courts save particular disfavor for restrictions on political speech, which occupies a place of special solicitude because of its central role in furthering self-governance.

Constitutional challenges to government speech restrictions find their way to court along two separate paths. First, a person who incurs a penalty for speaking may challenge the deprivation by arguing that the applicable statute or regulation was applied in an impermissibly speech-restrictive manner (an “as-applied” challenge). Second, a person who fears being penalized may bring a “facial” challenge by showing that a statute is “substantially” overbroad, sweeping in harmless or benign speech along with the speech that might permissibly be outlawed. Overbroad or vague regulations are disfavored because they will intimidate speakers into self-censoring, even if their speech was not the regulators’ intended target at all.

Judicial distaste for prior restraints, or for regulations that discriminate based on content or viewpoint, is where a legal challenge to a “one board” policy would begin. But the unique context of these regulations—the only people regulated are government policymakers, not ordinary citizens—adds a layer of complexity and uncertainty.

III. The First Amendment Goes (Halfway) to Work

A. Pickering, Garcetti, and the diminished rights of public employees

When the government acts as “regulator,” all of the normal proscriptions against content-based restrictions or prior restraints on speech apply with full force. But when the government acts as “employer,” courts view speech-restrictive regulations more deferentially, recognizing that freewheeling debate may be incompatible with effectively delivering government services. For instance, while offensive or unprofessional remarks normally are entitled to the full protection of the First Amendment, they can be grounds for disciplining a public school teacher or law enforcement officer, whose effectiveness depends on public confidence.

Just as with any other government speech restriction, a restraint on employee speech is subject to constitutional challenge either on its face or as applied to punitive action against a particular employee. In the latter case of an as-applied challenge, the Supreme Court has developed an analytical framework—beginning with its seminal 1968 decision in Pickering v. Board of Education —that attempts to strike a balance between the interests of the government and the speaker. In Pickering, Illinois schoolteacher Marvin Pickering was fired for his letter published in a local newspaper that urged readers to vote against a school bond referendum, arguing that the district—his employer—had misallocated money and attempted to silence employee critics. Pickering challenged his firing as a violation of his First Amendment rights but lost in Illinois state court. The Supreme Court, however, sided with Pickering. The justices held that “absent proof of false statements knowingly or recklessly made by him, a teacher’s exercise of his right to speak on issues of public importance may not furnish the basis for his dismissal from public employment.” Significantly, the Court rejected the argument that employee statements addressing matters of public concern lose their First Amendment protection if they are “sufficiently critical” of the employer. Thus was born the “Pickering balancing test,” which instructs courts to balance the employee’s interest in being heard on issues of public concern with the employer’s interest “in promoting the efficiency of the public services it performs through its employees.”

In Connick v. Myers, the justices sharpened the “public concern” aspect of Pickering, holding that there is no First Amendment protection against workplace sanctions—and thus no need to undertake the balancing test—when an employee speaks “not as a citizen upon matters of public concern, but instead as an employee upon matters only of personal interest,” such as her own compensation. Then in Garcetti v. Ceballos, the Court decided that when an employee speaks “pursuant to official duties”—such as, in that instance, a prosecutor’s act of writing a memo in furtherance of a work assignment—the speech receives no First Amendment protection because it is, effectively, the government’s own speech.

First Amendment safeguards weaken even further when an employee is regarded as a high-ranking policymaker. While an ordinary worker would be constitutionally protected against discharge for supporting the “wrong” candidate in an election, policymaking employees are subject to dismissal expressly because of their political views, if those views fail to align with the administration in power. One justification commonly advanced for extending diminished protection to upper-level employees is that a managerial employee’s speech will carry more weight and thus inherently be more likely to cause disruption if it is disloyal. Although circuits vary in the breadth of their application of the “policymaker” doctrine, it is universally accepted that the heads of government agencies cannot be forced to retain senior managers who do not share their policy views. However, there is a substantial question about whether the government’s ability to freely dismiss policymaking employees over political allegiance necessarily means that the government is equally free to punish policymaking employees in retaliation for speech. And there is reason to doubt that a member of a legislative body is the type of policymaking “employee” for whom the First Amendment carve-out was intended.

B. Employee gag rules and the First Amendment

Notwithstanding the decreased level of free speech protection recognized in the government workplace, a categorical restraint on publicly discussing work-related matters is widely recognized to be unconstitutional. There is a decisive distinction between imposing after-the-fact disciplinary consequences on a government employee whose speech disrupts the workplace (a decision that is reviewed relatively deferentially) versus restraining an entire category of government employees from ever being heard (which is reviewed more skeptically).

The Supreme Court’s signature case on prior restraints in public employment is United States v. National Treasury Employees Union, known as the NTEU case. There, the Court dealt with a First Amendment challenge to a federal regulation prohibiting government employees from accepting honorarium payments in exchange for speaking. The Court readily concluded that, even though the regulation did not entirely prohibit speaking, but merely removed an incentive to speak, it was still an unconstitutionally broad restraint. The Court deemed the government’s rationale—that some employees might be ethically compromised by accepting speaking fees from entities they regulate—too speculative to justify a sweeping restriction on all paid speeches by all employees. Significantly, the Court declined the government’s invitation to review the honorarium ban under a Pickering balancing-of-interests analysis. Rather, the justices held, a blanket prior restraint on speech demands weightier justification than a one-off disciplinary action against an individual speaker like Marvin Pickering:

[T]he Government’s burden is greater with respect to this statutory restriction on expression than with respect to an isolated disciplinary action. The Government must show that the interests of both potential audiences and a vast group of present and future employees in a broad range of present and future expression are outweighed by that expression’s ‘necessary impact on the actual operation’ of the Government.

Although the Court did not explicitly speak about the level of scrutiny it was applying, NTEU implicitly requires some degree of “tailoring” between the ill that the government purports to be addressing and the restriction it seeks to enforce.

Applying the NTEU standard, lower courts have found, overwhelmingly, that a government agency may neither forbid employees from discussing their work with the press and public nor require advance supervisory permission as a condition of speaking. In one noteworthy case, the Second U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals struck down a rule at New York City’s child welfare agency that required employees to refrain from discussing “any policies or activities of the Agency” with the news media and to refer any media calls to the agency’s public relations office. Most recently, the Ninth U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals found that the state highway patrol violated officers’ constitutional rights by enforcing a rule that forbade them from discussing the agency’s K-9 program with outsiders.

It is now clearly established that government agencies cannot enforce rules that forbid employees from discussing work-related matters with the press and public. A “one board” type of rule directed to all employees of a government agency invariably would be deemed unconstitutional under NTEU and its progeny. The question, then, is whether board members occupy a special unprotected class that can be silenced in ways that other government employees cannot.

IV. The First Amendment and Elected Officials

A. Check your rights at the voting booth?

Elected and appointed officials are a unique subcategory of the public workforce (if, indeed, they are properly categorized as “employees” at all). There is, remarkably, little certainty whether people occupying lawmaking positions enjoy the full-strength protection of the First Amendment or the second-class level recognized in the Court’s Connick/Garcetti jurisprudence—or something else entirely.

The Supreme Court has twice directly addressed the question of whether taking on an elected government position means forfeiting the full benefit of the First Amendment—and, on both occasions, ruled in favor of the speaker.

In Wood v. Georgia, the Court dealt with a First Amendment challenge brought by a sheriff convicted of contempt for several statements criticizing a judge for convening a grand jury investigation into the suppression of Black votes. The Supreme Court applied rigorous scrutiny and found that nothing less than a “serious degree of harm to the administration of law” could justify imposing contempt sanctions. Notably, the Court did not relax its usual demanding standard to justify contempt penalties for out-of-court speech, just because the speaker was an elected government official. To the contrary, the Court suggested that the sheriff might occupy an even more-protected First Amendment status by virtue of his office:

The petitioner was an elected official and had the right to enter the field of political controversy, particularly where his political life was at stake. … The role that elected officials play in our society makes it all the more imperative that they be allowed to freely express themselves on matters of current public importance.

The Court returned to the issue of elected officials’ free speech rights in a case challenging the Georgia House of Representatives’ refusal to seat the elected winner of a House seat, civil rights activist Julian Bond, because he advocated against the Vietnam war draft. When Bond challenged his disqualification, a three-judge district court deferentially reviewed the House’s decision merely for a rational basis and found no violation of Bond’s rights. But the Supreme Court reversed, rejecting the state’s contention that Bond could properly be excluded on the grounds of disloyalty to the United States. The Court did not expressly state what standard of review it applied but left little doubt that elected officials retain substantial First Amendment protection even against their own colleagues, particularly when their speech addresses matters of public concern:

[W]hile the State has an interest in requiring its legislators to swear to a belief in constitutional processes of government, surely the oath gives it no interest in limiting its legislators’ capacity to discuss their views of local or national policy. The manifest function of the First Amendment in a representative government requires that legislators be given the widest latitude to express their views on issues of policy.

The justices explicitly rejected the state’s contention that the First Amendment right to engage in unfettered political debate “only applies to the citizen-critic of his government” and not to government officials, implicitly putting the rights of elected officials on par with those of ordinary citizens.

Lower courts have overwhelmingly—though not unanimously—agreed that policymaking officials enjoy a level of free speech protection superior to that of lower-ranking public employees. In a 2005 case, the Second U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals ruled in favor of a New York school board member who was temporarily removed from her position in what she alleged to be retaliation for her conflict with other board members over various decisions, including the appointment of a replacement board member and the adoption of a diversity policy. Acknowledging that free speech rights sometimes diminish in the employer/employee context, the court said no such diminution applies when the plaintiff is an elected officeholder. Rather, the court concluded, the officeholder enjoys the same forceful protection against retaliation for speech as any other non-employee citizen. The federal Fifth U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals has similarly recognized a different First Amendment balance when the “employee” is an elected government official, because the “employer” in that scenario is not a higher-ranking official but the voters. Applying strict scrutiny to evaluate a censure order imposed on an elected Texas judge as punishment for his speech, the court wrote: “Our ‘employee’ is an elected official, about whom the public is obliged to inform itself, and the ‘employer’ is the public itself, at least in the practical sense, with the power to hire and fire. ... [A]s an elected holder of state office, his relationship with his employer differs from that of an ordinary state employee.”

In a recent high-profile case involving accusations of political retaliation by Florida Governor Ron DeSantis, the Eleventh U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals expressed deep skepticism that First Amendment protections diminish when the speaker is an elected official. The appeals court ruled that DeSantis could not remove an elected state prosecutor, Andrew Warren, on the basis of Warren’s statements that he disapproved of prosecuting people for seeking or performing abortions or for providing gender-affirming care to transgender youths. DeSantis defended his decision as a permissible exercise of the supervisory authority recognized by the Supreme Court in Pickering and Garcetti, but the judges hesitated to equate an independently elected government official with an employee answering to the governor. As to Pickering, the judges wrote: “The rationale undergirding Pickering does not support its application to elected officials. … DeSantis does not manage Warren as a traditional employer would.” As to Garcetti, the judges were even more dubious:

Garcetti’s rationale makes little sense for elected officials. … [E]lected officials do not exercise a significant degree of control over other elected officials. … [O]ne legislator cannot control or manage another. Each legislator’s constituency does that.

Ultimately, the appeals court found it unnecessary to decide whether to apply the “public employee” level of protection or the “real-world” level of protection, because DeSantis’ actions—justified solely by hoped-for political gain—fell short of satisfying any level of First Amendment scrutiny.

Applying the Garcetti level of control to the speech of governing board members—and treating the board’s majority as, in effect, the “employer”—would invite all manner of potential abuses, since everything a board member says about board business could be regarded as unprotected “official-duty” speech. As one commentator perceptively observed:

A legislative majority empowered to police the speech of its members through the government speech doctrine possesses a nuclear weapon, the deployment of which obliterates any potential free speech considerations raised by the silencing of others. For example, an elected majority might vote to prevent any elected official from speaking to the news media.

Based on decades’ worth of precedent, there is essentially no indication that courts are prepared to afford members of lawmaking boards a stepped-down level of constitutional protection that would deprive them of the benefit of, at the very least, the NTEU standard. Since we know that rules against discussing work-related matters with the public are unconstitutional when applied to the workforce of an agency as a whole, a “one board” rule would be constitutional only if legislative board members had fewer rights than other employees. But in fact, the opposite seems to be the case. If Wood and Bond were the Supreme Court’s last word on the rights of elected policymakers, the answer to the question “Can a policymaking board enforce a ‘one voice’ speaking restriction?” would be an unequivocal no. But a more recent First Amendment decision introduces at least a modicum of uncertainty.

B. Wilson’s whiff: A missed opportunity

A 2022 case, Houston Community College System v. Wilson, gave the Supreme Court the opportunity to clarify the metes-and-bounds of First Amendment rights in elected office. But the Court decided the issue in a narrow, fact-specific way without grappling with the broader constitutional questions the case raised.

The Wilson case originated when a Texas community college board imposed sanctions on an elected board member, David B. Wilson, who became known for his caustic criticism of both the college and his board colleagues. Wilson alienated the board not only with his inflammatory remarks but also by twice suing the board over its voting procedures and hiring a private investigator to investigate the college and one of his fellow trustees. In January 2018, the board voted to censure Wilson—its stiffest available sanction—directing him to cease conduct detrimental to the college or the board and threatening that repeat offenses would be grounds for unspecified additional disciplinary measures.

Wilson sued alleging that the sanctions violated his First Amendment rights. A federal district court dismissed Wilson’s case for failure to identify a cognizable injury. But the Fifth U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals reinstated the case, relying on precedent in the setting of constitutional challenges to censures of judges, which have been deemed to constitute actionable acts of retaliation. That set up a showdown at the U.S. Supreme Court.

In a March 2022 ruling, the Court unanimously reversed the Fifth Circuit and found that a mere censure cannot support an elected official’s First Amendment retaliation claim. The Court rested its ruling against Wilson on three bases. First, the Court observed that censure is a time-honored feature of elected bodies, widely accepted as an extension of those bodies’ ability to police their own internal affairs. Second, the Court regarded the punishment of censure to be too immaterial to qualify as an actionable act of retaliation—particularly when those on both sides are elected officials, who put their character at issue when they voluntarily take on the mantle of public office. Finally, the Court noted that the retaliatory act of which Wilson complained was itself a form of constitutionally protected counterspeech: “The First Amendment surely promises an elected representative like Mr. Wilson the right to speak freely on questions of government policy. But just as surely, it cannot be used as a weapon to silence other representatives seeking to do the same.”

There is considerable reason to doubt whether Wilson was correctly decided. The notion that a censure resolution is a necessary tool that government bodies must be able to wield to distance themselves from an obnoxious colleague ignores the Court’s long-standing preference for counterspeech, rather than government sanction, as the proper way to disavow a distasteful message. The Court did not even attempt to explain why counterspeech by Wilson’s eight colleagues on the board would not just as effectively have conveyed their disapproval, without invoking the mechanism of a governmental vote. Indeed, the fact that a censure resolution does nothing other than send a message has been critical to courts’ conclusion that censure is too immaterial to constitute actionable retaliation. If a censure resolution is merely a form of counterspeech, it is fair to ask why board members do not simply engage in actual counterspeech; evidently, they see the censure as being a more weighty sanction, of the sort that might chill a person of ordinary firmness from further expression.

One infirmity in the Wilson Court’s reasoning was assuming that the act of voting for a censure resolution qualifies as constitutionally protected speech on the part of the other board members—an assumption in tension with the Court’s ruling in Nevada Commission on Ethics v. Carrigan, which the Wilson court entirely failed to acknowledge. In Carrigan, a unanimous Court rejected a First Amendment-based challenge to a state ethics statute requiring elected officials to recuse from voting on matters that put them in positions of conflicted loyalty, such as matters affecting close family members. A city council member challenged the statute after a state ethics board found him in violation for voting in favor of a project benefiting his campaign manager, a longtime friend. But the Court declined to find any First Amendment interest in a city council member’s vote, with Justice Antonin Scalia writing: “[A] legislator’s vote is the commitment of his apportioned share of the legislature’s power to the passage or defeat of a particular proposal. The legislative power thus committed is not personal to the legislator but belongs to the people; the legislator has no personal right to it.” A vote merely discloses what the elected official believes but is not itself an expressive act, Scalia wrote. The Court, he said, “has rejected the notion that the First Amendment confers a right to use governmental mechanics to convey a message.”

It is possible that the Court might have reached the same outcome in Wilson removing the errant justification that a censure vote constitutes constitutionally protected expression. But it is also possible that—without the dynamic of a “speaker versus speaker” contest, with First Amendment interests on both sides—the Court might have balanced the equities differently. In any event, Wilson stands as the Court’s most recent word on the free speech rights of elected officials—albeit, in the Court’s own words, “a narrow one” —and it can be expected to influence the disposition of a future constitutional challenge to the enforcement of a “one board” policy.

C. The Big Chill: How big must it be?

The Supreme Court’s disposition of Wilson points to a broader unresolved constitutional issue: How substantial of a deprivation must a speaker suffer for purposes of supporting a retaliation claim under the First Amendment? The Supreme Court has indicated that any government punishment directed at silencing an employee’s constitutionally protected speech—even something as inconsequential as canceling a scheduled birthday party—could be enough to sustain a retaliation case. Some—but not all—lower courts have faithfully applied Rutan v. Republican Party of Illinois’ guidance and found that even a reprimand or other immaterial change in working conditions can be grounds for a First Amendment retaliation case. As the Ninth Circuit has stated the applicable standard:

The precise nature of the retaliation is not critical to the inquiry in First Amendment retaliation cases. The goal is to prevent, or redress, actions by a government employer that chill the exercise of protected First Amendment rights. … Depending on the circumstances, even minor acts of retaliation can infringe on an employee’s First Amendment rights.

This approach makes intuitive sense. If the goal of the law is to deter ill-motivated government officials who act with the intent to silence disfavored speakers, then it should not matter what method the censors choose to send their message of intimidation. Surely, no viewer of The Godfather would suggest that actor John Marley’s character, fictional movie producer Jack Woltz, was not thoroughly chilled to awaken to a decapitated horse’s head in his bed, even though the gesture did not deprive him of any benefit of employment.

But adherence to Rutan is not unanimous. Several circuits have imported the law of Title VII employment discrimination cases into the law of First Amendment retaliation, finding that only a materially adverse employment action—such as dismissal, demotion, or a comparably tangible deprivation—is enough to support a retaliation claim. So, for example, a New Mexico schoolteacher who alleged that she was punished for labor union activity by being put on a regimen of intensive monitoring and supervisory meetings did not meet the threshold of the Tenth U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals for a sufficiently material adverse action, because there was no actual change in her employment status.

This “adverse employment action” approach is difficult to reconcile with the Supreme Court’s First Amendment retaliation jurisprudence. As Judge Richard Posner explained in a carefully reasoned Seventh U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals opinion, it makes no sense to confine the reach of constitutional claims under 42 U.S.C. § 1983 to material changes in working conditions, because neither the First Amendment nor Section 1983 is limited to employee/employer cases. “Any deprivation under color of law that is likely to deter the exercise of free speech, whether by an employee or anyone else, is actionable,” he wrote.

To add another layer of complexity, the level of “adversity” necessary to sustain a retaliation claim may vary when the speaker is an elected official, particularly where the punishment is meted out by fellow elected officials. Wilson and its forerunner cases suggest that the same type of government intimidation tactics that would intimidate a normal person into silence might not pierce the thicker skin of a player in the political arena.

In a preview of what a challenge to punishment for violating a “one board” rule might look like, the Ninth Circuit disposed of a First Amendment claim by an elected school board member, Ken Blair, who faced retaliation from his colleagues after discussing his decision to cast a dissenting vote with a newspaper reporter. While the court acknowledged that Blair had all the classic makings of a First Amendment retaliation case, what defeated his claim was the nature of the adverse action: removal from his position as vice-chair by vote of the other four board members, which the court viewed as “a minor indignity.” In language that would echo a decade later in the Supreme Court’s Wilson decision, the Ninth Circuit wrote that the mere loss of a leadership title was too immaterial to sustain a retaliation claim, because Blair retained his full authority as a board member: “[M]ore is fair in electoral politics than in other contexts. … [T]he First Amendment does not succor casualties of the regular functioning of the political process.”

The Blair decision is part of a trio of influential appellate rulings rejecting free speech claims by elected officials on the grounds that the sanctions imposed were insufficiently severe. In Zilich v. Longo, the Sixth U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals decided that a former Ohio city council member had no First Amendment case based on a resolution denouncing him and accusing him of collecting a salary he was ineligible to receive, because the resolution carried no concrete penalty: “The First Amendment is not an instrument designed to outlaw partisan voting or petty political bickering through the adoption of legislative resolutions.” And in Phelan v. Laramie County Community College Board of Trustees, the Tenth Circuit ruled that a community college board’s censure resolution did not trigger any First Amendment scrutiny at all, because it carried no penalties and imposed no restrictions on the censured board member’s ability to perform her duties. The Zilich/Phelan/Blair triumvirate has been invoked dozens of times by lower courts in concluding that government board members have no First Amendment protection against condemnation or other immaterial punishments imposed by fellow board members.

In a recent decision putting something of a limiting gloss on Blair, the Ninth Circuit revisited the issue of materiality in the context of a retaliation claim brought by an Oregon state senator, Brian Boquist. After Boquist made inflammatory remarks toward law enforcement that were viewed as veiled threats, his senate colleagues imposed sanctions requiring him to give 12-hour advance notice before entering the statehouse so security could be increased. Although the 12-hour rule did not deprive Boquist of any tangible benefits of his office—he could still vote, speak, and otherwise exercise the powers of a senator—the Ninth Circuit found the sanction to be sufficiently material to sustain his retaliation claim. The judges said that taking part in the political process means elected officials are expected to endure some indignities that ordinary speakers are not, but that does not give legislative bodies a blank check to retaliate against their members. Neither Blair nor the Supreme Court’s Wilson, they said, meant “that an adverse action against an elected official could never be sufficiently material to raise an actionable claim for First Amendment retaliation.”

The Boquist decision captures where the law of First Amendment retaliation appears likely to coalesce: Elected officials have substantial free speech protection exceeding that of rank-and-file government employees, but they must make a more substantial showing of harm—more than Rutan’s proverbial canceled birthday celebration—out of deference to the countervailing free speech interests of their critics. Based on this body of precedent, an “as-applied” challenge by a board member penalized for defying a “one board” speech rule would predictably face tougher sledding than a facial constitutional challenge, especially if the punishment stopped short of stripping the dissenting board member of voting authority or other core trappings of the office.

V. “One Board” Rules and the First Amendment

A. Speaking with one voice—like it or not

For years, journalists covering the public school system in Spokane, Washington, have encountered frustration in trying to interview elected school board members about district policy matters: None of them, except the president, is allowed to speak to the media. In an interview, the board president explained that the reason for the rule is “to assure that decisions the board has made are represented by a single voice.” One candidate seeking a board seat told a reporter that allowing more than one member to speak to the media “could lead to the public misinterpreting things.”

There is no comprehensive national database of the policies that govern the speech of members of elected and appointed boards. But anecdotally, a search of news reports and publicly available board rulebooks turns up dozens of examples of constitutionally dubious “one voice” policies across state and local government entities. They have been imposed on local and state governing board members, college trustees, and school board members throughout the country. The existence of these rules limits the ability of journalists to effectively cover controversies when there are differences of opinion within policymaking boards.

An online search readily turns up examples of local government policies that do not merely restrict elected officials’ ability to share their candid thoughts with the news media but actually compel them to espouse positions they may not hold. An example appears in the trustee rulebook for Mississippi’s Jackson College, which states that members are required to refer any media inquiries to the chair of the board without answering them and that trustees “will support the legitimacy and authority of Board decisions, regardless of the member’s personal position on the issue.” Another appears in the handbook for town council members in Thiensville, Wisconsin, which states: “When you speak to the public, voice the official Board stand, not your own individual opinion.”

More nuanced policies indicate that only designated officials—typically, the board chair—may speak publicly on behalf of the board but leave open the opportunity to speak in an individual capacity. For instance, a city ordinance in Sturgeon Bay, Wisconsin, simply instructs elected city council members to avoid creating the impression that their personal opinions are the official position of the council but does not purport to impose any penalties: “When communicating with the media, council members should clearly differentiate between personal opinions and the official position of the city.” Similarly, the DeKalb County, Georgia, school district instructs its elected board members: “Individual Board members may respond to media inquiries as they deem appropriate; however that individual speaks in his or her individual capacity and not on behalf of the Board as a whole and should make that clear in working with the media.”

On occasion, attempts to silence dissident board members have provoked pushback. A Houston-area school board agreed to soften its “one board” policy after two members complained that they felt constrained in being able to discuss their disagreement with disputed issues, including cost overruns in building a stadium. In 2014, a New Hampshire school district revised its “one board” policy—which forbade anyone but the board chair from speaking to the press and required all members to support the majority’s decisions—in the face of a threatened lawsuit by the New Hampshire Civil Liberties Union. Some trustees of Shreveport’s Caddo Parish school district balked when a “one board” rule was submitted for a vote—with one calling it a maneuver “to shut the media out”—but the policy ended up passing. No facial challenge, however, appears to have yet reached the courthouse, so there is no authoritative word on how judges will assess the constitutional issues.

B. The reputation justification

Whenever a government regulation restrains speech, the critical inquiry will be the strength of the regulator’s justification. If a justification is as compelling as the public’s physical safety, even a stringent restraint on speech can be constitutional.

The primary rationale that has been put forward for restraining board members from expressing dissenting views is to promote a favorable image of the agency. For instance, several cities have cookie-cutter “one voice” policies on the books that discourage city council members from expressing dissent from a policy decision in explicitly reputation-based terms:

Council members will frequently be asked to explain a council action or to give their opinion about an issue as they meet and talk with constituents in the community. .... Objectively present the council’s collective decision or direction, even when you may not agree. … Explaining council decisions, without giving your personal criticism of the council’s actions, will serve to strengthen the community’s image of the city council.

In the event of a facial challenge to a “one board” rule, any justification based on preserving a government agency’s reputation would run squarely into decades of adverse U.S. Supreme Court precedent.

In Landmark Communications, Inc. v. Virginia, the justices found that a law criminalizing the disclosure of truthful information about confidential judicial misconduct investigations violated the First Amendment. The case was brought by a Virginia newspaper convicted and fined for violating the prohibition, and the justices confined themselves to the narrow question of whether third-party nonparticipants in the investigation could be penalized for their accurate disclosures. The Court concluded that they could not. Acknowledging that promoting discussion of governmental affairs was central to the purpose of the First Amendment, the justices found no overriding state interest that could justify criminalizing the newspaper’s speech. Specifically, the Court rejected the idea that either the reputation of individual judges under investigation, or the reputation of the judiciary as a whole, constituted the compelling state interest necessary to legitimize criminalizing speech. To the contrary, Chief Justice Warren Burger wrote for the unanimous Court, suppressing disclosures unflattering to judges would have the opposite of its intended effect, breeding skepticism and distrust.

A decade-and-a-half later, the Court expanded on Landmark in Butterworth v. Smith, which dealt with a Florida law forbidding witnesses in grand jury proceedings from ever disclosing anything about their testimony. Unlike in Landmark, the law at issue in Butterworth applied to speech by actual participants in the grand jury investigation, but the Court found that distinction immaterial. As in Landmark, the Court began by recognizing that speech relating to allegations of government misconduct—the speech that the plaintiff in Butterworth sought to engage in—was “at the core of the First Amendment.” The state offered multiple justifications for the statute, which the Court readily dispensed with; for instance, the rationale that secrecy was necessary to protect the independence of grand jurors’ deliberations, or avoid tipping off a suspect that he was under investigation, could not justify an indefinite prohibition enduring beyond the jury’s term. That left the state’s concern for preserving the reputations of people whose names might arise as suspects but who end up facing no charges. But Justice William Rehnquist wrote for the unanimous court: “[O]ur decisions establish that absent exceptional circumstances, reputational interests alone cannot justify the proscription of truthful speech.”

Applying the principles of Landmark and Butterworth, court after court has rejected the assertion that speakers can be silenced out of concern for the reputation of government officials, agencies, or processes. For instance, an appellate court found that Florida could not penalize a journalist under a statute outlawing disclosure of information learned during an internal law enforcement investigation, because there was no compelling state interest in protecting wrongfully accused officers against reputational harm: “In a free society, the public’s trust in an official’s reputation is won by greater transparency, not the silencing of criticism.” In particular, mandatory confidentiality laws that forbid disclosing information about investigative proceedings involving judges or attorneys do not withstand constitutional scrutiny, when their justification is to preserve the image of people under investigation. As a federal district court stated, ruling in favor of a complainant who was threatened with contempt for violating a Florida Supreme Court rule against disclosing information about unresolved attorney misconduct complaints:

The idea that the suppression of truthful criticism of lawyers would somehow enhance or protect the reputation of the Bar is not persuasive. To the contrary, continuing the prohibitory effect of the Rule after a grievance against an attorney is found to be meritorious is far more likely to engender suspicion than foster confidence.

This resounding rejection of reputation as a basis for gagging speakers from addressing matters of public concern would present a formidable headwind for any agency attempting to defend a “one board” restriction.

C. Challenging a penalty for “unauthorized political speech”

In a case that presaged today’s debate over compulsory “one voice” policies, a federal district judge wrote in the context of a retaliation claim brought by an elected city council member, who was punished after clashing with her colleagues over budget issues:

Many of the reasons for restrictions on employee speech appear to apply with much less force in the context of elected officials. … [B]ecause elected officials to a political body represent different constituencies, there would seem to be far less concern that they speak with one voice. In fact, debate and diversity of opinion among elected officials are often touted as positives in the public sphere.” …

An elected official may well disagree with and press for changes to existing laws and policies; indeed, she may have been elected for that very purpose. Nor can a legislator be prohibited from holding a minority political view; that represents the democratic process functioning as intended.

Regardless of whether elected officials occupy the same constitutional status as rank-and-file public employees or sit on a more-protected tier, a policy forbidding an elected official from expressing dissenting viewpoints clearly is vulnerable to a First Amendment challenge.

The likely starting point to any challenge would be the Supreme Court’s decision in Republican Party of Minnesota v. White, which dealt with a state statute that forbade judicial candidates from publicly taking positions on contested legal or political issues, with penalties including removal from office for incumbents or professional license sanctions for non-incumbent candidates. The Court found the statute unconstitutional, ruling in favor of a would-be judicial candidate who had been threatened with penalties during a prior campaign. The Court did not grapple much with the proper level of scrutiny to apply, citing (seemingly, with approval) the circuit court’s decision to review the statute under strict scrutiny. Applying that standard, the majority concluded that the statute was insufficiently well-tailored. Among its flaws, Justice Antonin Scalia wrote, was that the prohibition was “woefully under inclusive” if justified by a desire to create the impression of impartiality, because judges, or future judicial candidates, would remain free to express opinions on contested issues at any time other than while campaigning.

Assuming that a “one board” rule is analyzed either as a content-based restriction on speech (as the Court did in White) or as a prior restraint, then strict scrutiny will apply, and the regulation will be unconstitutional unless it is shown to be the most narrowly tailored means of achieving a compelling government objective. But a court might instead consider a facial challenge to a “one board” rule under the framework recognized in NTEU for restrictions on employee speech, rather than applying the White standard for candidate speech. Under NTEU, a “one board” regulation will be invalid unless the regulator shows that the restriction is so concretely necessary to prevent interference with government operations as to override both the speakers’ and the audiences’ interests in expression. Although this standard is not the least-restrictive-means standard that would apply outside the workplace, it still requires showing both that a legitimate government interest exists and that the restriction is well-tailored to achieve it. So, regardless of the analysis that applies, the key inquiry will be whether the government has presented a substantial reason for silencing public officials from speaking.

As we have seen, cultivating a favorable public impression of the board is quite unlikely to qualify as a compelling objective; indeed, it may be a wholly illegitimate one. Nor does it seem likely that a court would find the government’s related interest in suppressing dissent to be of any value in a First Amendment analysis, much less compelling enough to justify a prior restraint. This is especially true when—as in the case of school boards, city and county commissions, and some college trustee boards—the position is an elected one answerable to voters. Regulations aimed at dampening political dissent have been held unconstitutional for nearly a century, even when the speech is far more incendiary, or of far lower value, than expressing disagreement with a board vote. The Supreme Court recognized in its landmark Sullivan opinion that constitutionally protected speech “may well include vehement, caustic, and sometimes unpleasantly sharp attacks on government and public officials.”

Even if a sufficiently persuasive objective did exist, “tailoring” requires a tight fit between the restriction and the substantive ill that the government is trying to avoid. One obvious infirmity in the publicly available examples of “one board” policies is that they appear unlimited in duration. None carries an expiration date that would, for example, allow a board member to freely criticize board votes when it is time to campaign for reelection. Indefinite restraints on speech are especially difficult to justify and are rarely upheld, as opposed to restraints that temporarily forbid disclosing information when necessary to avoid a serious and concrete harm, such as compromising an ongoing criminal investigation.

A “narrow tailoring” analysis will also look at whether the government agency could achieve its objective equally effectively by way of less speech-restrictive means. If the government’s objective is to avoid undermining the legitimacy of board decisions in the eyes of the public, a “one board” policy that forbids all dissenting speech seems overbroad to accomplish that task. The government would have to demonstrate that the First Amendment’s preferred remedy—counter-speech by other board members—would not achieve the objective as effectively as silencing or punishing dissenting members. As courts have recognized in the context of overbroad prohibitions on divulging complaints against lawyers or public officials, it is deeply questionable that suppressing criticism furthers the objective of promoting public confidence. The rationale offered to justify the “one board” rule in Spokane Public Schools—that the public might be confused if board members sent conflicting messages —is unlikely to suffice to justify a wholesale ban on speaking, since it is entirely possible that a dissenting board member will speak without causing any confusion, acknowledging that her position does not reflect the majority’s vote. Far from “confusing” the public, allowing each side of a disputed vote to be publicly heard seems likely to enhance public understanding as to whether certain policies are or are not universally supported by board members of different backgrounds, ideologies, and constituencies.

Particularly in the context of speech by elected representatives, there is a substantial First Amendment interest in receiving as well as delivering speech. The Supreme Court has not delineated the metes-and-bounds of the First Amendment right to receive information, but it undeniably exists to some extent, particularly in the context of political speech. If an elected board member is willing to share his explanation for casting a dissenting vote, and a voter is interested in receiving that explanation, then any regulation that interferes with that exchange of ideas implicates the First Amendment rights of the voter —who, unlike the elected official, has not voluntarily surrendered any freedoms in exchange for a government position. As the Supreme Court recognized in Julian Bond’s case: “Legislators have an obligation to take positions on controversial political questions so that their constituents can be fully informed by them, and be better able to assess their qualifications for office(.)”

Significantly, one factor that courts have found persuasive in evaluating public employees’ First Amendment claims is whether the employee sought to engage the general public as opposed to merely speaking within the workplace. This makes sense, because Garcetti is all about speech made as part of official work duties, and no employee is “assigned” to engage in public whistleblowing. Because “one board” rules exclusively restrict speech directed to external audiences, these rules target the speech that the First Amendment most vigorously protects.

Even where courts have been unwilling to entertain First Amendment retaliation claims by elected officials, the rationale for those rulings cuts against, not in favor of, “one board” regulations. The rationale that a censure is not actionable is based on a desire to promote the wide-open exchange of differing views among board members. But a regulation that prevents one side from participating in debating contested political issues has the opposite effect. It insulates government officials against criticism of their decisions by the critics who are in the best position to offer an informed inside perspective. Accordingly, the Blair/Zilich/Longo line of cases does not support the conclusion that a categorical prohibition on expressing dissenting viewpoints is constitutional, even if violation is punishable only by censure.

VI. Conclusion

Restricting speech by dissenting members of government boards implicates several foundational First Amendment principles that are beyond debate: Blanket prior restraints on speech are presumptively unconstitutional, as are viewpoint-based restrictions that apply only to one side in a contested debate. Preserving the reputation of government agencies and officials is too insubstantial of a concern to overcome the First Amendment’s strong disfavor for prior restraints or viewpoint-based restrictions. Accepting a government office—including an elected or appointed position—does not divest a speaker of all First Amendment rights. This much we know for certain.

Based on those foundational principles, a “one board” rule—particularly one making no distinction between official-capacity speech and personal speech—appears quite unlikely to survive a First Amendment challenge. But, given the Court’s recent resolution of the Wilson case, there is at least a kernel of doubt about the justices’ willingness to protect the speech rights of dissenting elected officials. In the event of an as-applied challenge by a board member sanctioned for running afoul of a “one board” prohibition, the disposition might well depend on whether the penalty was regarded as a form of government counterspeech or otherwise considered immaterial. But a facial constitutional challenge should face no such impediment. The existence of any uncertainty points to the need for the Court to take its earliest opportunity to clarify, once and for all, that assuming a legislative position is not a ticket to second-class First Amendment status.

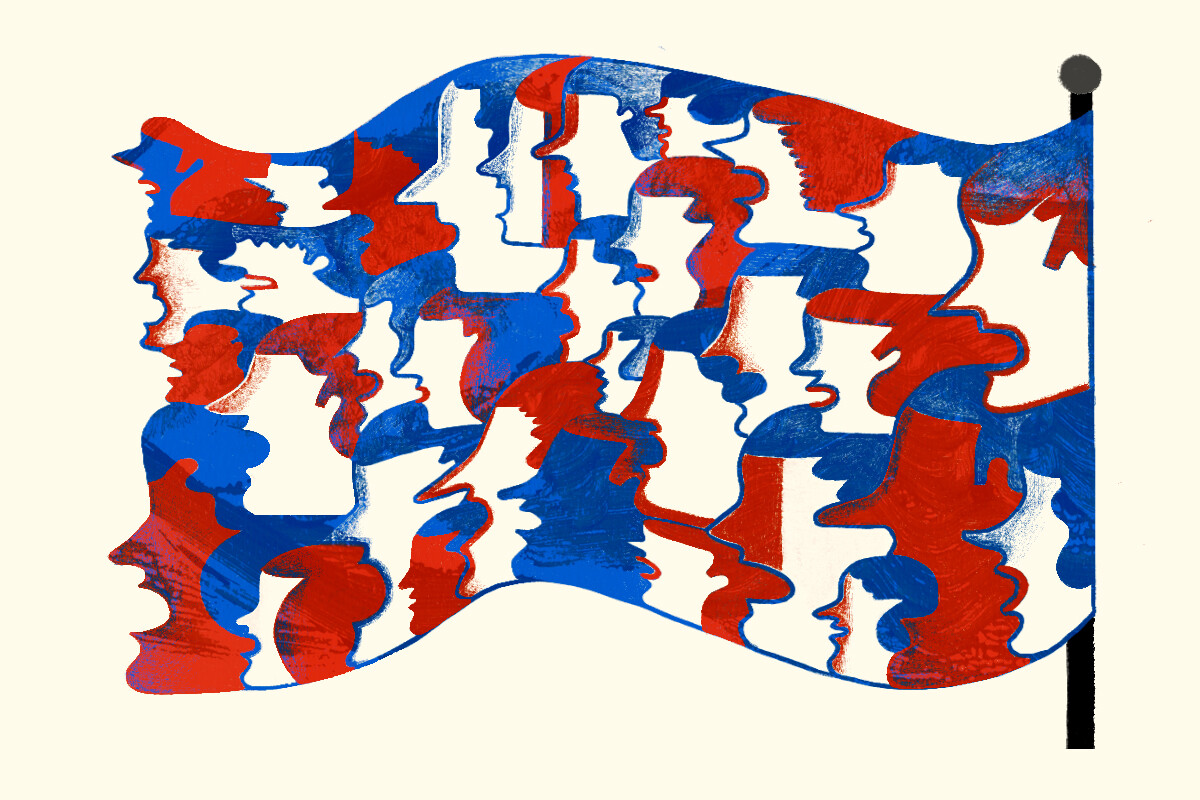

Beyond the self-evident constitutional issues, there are compelling public policy imperatives for protecting minority viewpoints within elected bodies. We live in an especially politically divisive time, at which “culture wars” are overtaking school boards, university governing boards, and other state-and-local legislative bodies. The Supreme Court’s admonition six decades ago—that “[t[he role that elected officials play in our society makes it all the more imperative that they be allowed to freely express themselves on matters of current public importance” —is arguably even more resonant in the current political environment, when policy decisions are being made on the basis of conspiracy theories and manipulative falsehoods. If a school board votes 3-2 to enact a book-banning policy, the electorate has an obvious interest in hearing the dissenting members’ rationale—but a “one board” rule leaves only the proponents free to speak favorably about the policy, a classic illustration of why viewpoint discrimination is so pernicious. The theory that free speech is intrinsic to self-governance assumes that the give-and-take of competing ideas will produce better policy outcomes and that misguided policy decisions can be corrected if enough public pressure is brought to bear. The notion that elected representatives on the short end of a 3-2 vote lose their right to enlist public support to turn around the outcome runs counter to basic democratic principles. Within a democracy, the free exchange of ideas is understood to be the means to arrive at genuine consensus—as opposed to restraining the exchange of ideas to create the illusion of consensus.

© 2024, Frank D. LoMonte.

Cite as: Frank D. LoMonte, Forced Unanimity and the First Amendment, 24-16 Knight First Amend. Inst. (Oct. 11, 2024), https://knightcolumbia.org/content/forced-unanimity-and-the-first-amendment[https://perma.cc/3BZV-SDPH].

Howard B. Owens, Five School Districts in Genesee County Restrict Speech for Board Members, The Batavian (May 14, 2018), https://www.thebatavian.com/howard-b-owens/five-school-districts-in-genesee-county-restrict-speech-for-board-members/515743.

See Nebraska Press Ass’n v. Stuart, 427 U.S. 539, 559 (1976) (“[P]rior restraints on speech and publication are the most serious and the least tolerable infringement on First Amendment rights.”); Near v. Minnesota, 283 U.S. 697, 731 (1931) (stating that “it has been generally, if not universally, considered that it is the chief purpose of the guaranty [of the First Amendment] to prevent previous restraints upon publication”).

See United States v. Hansen, 599 U.S. 762, 769-70 (2023) (“Overbroad laws “may deter or ‘chill’ constitutionally protected speech,” and if would-be speakers remain silent, society will lose their contributions to the marketplace of ideas.”) (quoting Virginia v. Hicks, 539 U.S. 113, 119 (2003) (internal quotes omitted). See also Maria Brooke Tusk, No-Citation Rules as a Prior Restraint on Attorney Speech, 103 Colum. L. Rev. 1202, 1223 (2003) (asserting that “[t]he most commonly touted justification of the Court’s predilection for subsequent punishment is that prior restraint does not permit certain expression to ever enter the marketplace of ideas, thereby imposing a more significant burden on speech.”).

Smith v. Daily Mail Publ’g Co., 443 U.S. 97, 103 (1979).

Twitter, Inc. v. Sessions, 263 F.Supp.3d 803, 812 (N.D. Cal. 2017); see also Facebook, Inc. v. Pepe, 241 A.3d 248 (D.C. App. 2020) (finding that even concern for prematurely revealing criminal defendant’s defense strategy was not sufficient to justify restraining technology company from sharing information about its receipt of warrant for disclosure of electronic communications).

See Nebraska Press Ass’n, 427 U.S. at 570 (“This Court has frequently denied that First Amendment rights are absolute and has consistently rejected the proposition that a prior restraint can never be employed.”).

See Procter & Gamble Co. v. Bankers Trust Co., 78 F.3d 219, 227 (6th Cir. 1996) (“[T]he Supreme Court has never upheld a prior restraint, even faced with the competing interest of national security or the Sixth Amendment right to a fair trial.”); Matter of Providence Journ., 820 F.2d 1342, 1348 (1st Cir. 1986) (“In its nearly two centuries of existence, the Supreme Court has never upheld a prior restraint on pure speech.”).

United States v. Playboy Ent’mt, Grp., Inc., 529 U.S. 803, 813 (2000) (“If a statute regulates speech based on its content, it must be narrowly tailored to promote a compelling Government interest.”); see also Rebecca L. Brown, The Harm Principle and Free Speech, 89 S. Cal. L. Rev. 953, 955 (2016) (observing that, as of 2016, “there has been no case in which a majority of the Supreme Court has found a government interest sufficient to redeem a law that it had analyzed as content-based”).

Citizens United v. Fed’l Elections Comm’n, 558 U.S. 310, 340 (2010).

Rosenberger v. Rector and Visitors of Univ. of Va., 515 U.S. 819, 829 (1995) (“When the government targets not subject matter, but particular views taken by speakers on a subject, the violation of the First Amendment is all the more blatant. ... Viewpoint discrimination is thus an egregious form of content discrimination.”).

See New York Times Co. v. Sullivan, 376 U.S. 254, 270 (1964) (asserting that “debate on public issues should be uninhibited, robust, and wide-open”).

Wm. Grayson Lambert, Toward A Better Understanding of Ripeness and Free Speech Claims, 65 S.C. L. Rev. 411, 434 (2013).

See Broadrick v. Oklahoma, 413 U.S. 601, 615 (1973) (opining that “particularly where conduct, and not merely speech is involved, we believe that the overbreadth of a statute must not only be real, but substantial as well, judged in relation to the statute's plainly legitimate sweep”).

See United States v. Wallington, 889 F.2d 573, 576 (5th Cir. 1989) (“The constitutional defect of an overbroad restraint on speech lies in the risk that the wide sweep of the restraint may chill protected expression.”).

See Helen Norton, Constraining Public Employee Speech: Government’s Control of its Workers’ Speech to Protect its Own Expression, 59 Duke L.J. 1, 8 (2009) (observing that “the Court has granted government more power to regulate the speech of its workers than that of its citizens generally”).

See, e.g., Grutzmacher v. Howard County, 851 F. 3d 332 (4th Cir. 2017) (finding that former fire department officer could not prevail on First Amendment retaliation claims after he was dismissed for “liking” and posting insulting comments on social media about liberals, some of which had racial overtones); Munroe v. Central Bucks School Dist., 805 F. 3d 454 (3d Cir. 2015) (affirming dismissal of teacher’s First Amendment claim for blog posts using insults like “jerk” and “dunderhead” to refer to unnamed students in her class, deeming the remarks to be unprotected because they addressed no matters of public concern).

391 U.S. 563 (1968).

Id. at 566-67.

Id. at 574.

Id. at 570.

Id. at 568.

Connick v. Myers, 461 U.S. 138, 147 (1983).

Garcetti v. Ceballos, 547 U.S. 410, 444 (2006). Notably, the Court put a limiting gloss on Garcetti in Lane v. Franks, 573 U.S. 228 (2014), emphasizing that speech is unprotected only if speaking is itself a duty of the employee’s job, not merely because it draws on knowledge gained in the course of government employment.

See Rose v. Stephens, 291 F.3d 917, 921-22 (6th Cir. 2002) (surveying varying approaches taken by federal circuits, with Ninth Circuit treating “policymaker” status as absolute bar to claiming First Amendment retaliation, while other circuits treat “policymaker” status as dispositive only where the speech at issue relates to the employee’s “political affiliation or substantive policy views,” leaving open the possibility of a retaliation claim in other circumstances); see also Lathus v. City of Huntington Beach, 56 F.4th 1238, 1242-43 (9th Cir. 2023) (finding that municipal advisory board member could not mount First Amendment claim against city council member who appointed her to represent the council member’s views, then removed her after a disagreement, because “a councilperson is entitled to an appointee who represents her political outlook and priorities”).

See McEvoy v. Spencer, 124 F.3d 92, 103 (2d Cir. 1997) (“Common sense tells us that the expressive activities of a highly placed supervisory, confidential, policymaking, or advisory employee will be more disruptive to the operation of the workplace than similar activity by a low level employee with little authority or discretion.”).

See Wilbur v. Mahan, 3 F.3d 214, 217-18 (9th Cir. 1993) (explaining that concern behind “policymaker” exception “is with the effects on the operations of government of forcing a public official to hire, or retain, in a confidential or policymaking job, persons who are not his political friends and may be his political enemies”).

See Hoffman v. DeWitt Cnty., 176 F.Supp.3d 795, 811-12 (C.D. Ill. 2016) (rejecting argument that elected county governing board member was subject to diminished “policymaker” level of First Amendment protection in bringing retaliation claim against fellow county officials who arranged his retaliatory arrest and prosecution, and stating that the plaintiff “is an elected official who is being prevented from representing his constituents rather than an employee silenced by the executive who appointed him”). See also infra Sec. IV(A).

513 U.S. 454 (1995).

Id. at 469-70.

Id. at 476-77.

Id. at 467.

Id. at 468.

See Swartzwelder v. McNeilly, 297 F.3d 228, 236-37 (3d Cir. 2002) (making this point in the context of upholding injunction against city regulation that forbade police officers from giving expert testimony without prior supervisory approval).

Frank D. LoMonte, Putting the “Public” Back into Public Employment: A Roadmap for Challenging Prior Restraints That Prohibit Government Employees from Speaking to the News Media, 68 U. Kan. L. Rev. 1, 14 (2019) (“Following NTEU, lower courts regularly struck down gag orders imposed by state and local agencies that purported to require employer approval of all contact with the media. Indeed, no ‘prior restraint’ on public employee speech, even outside the context of media interviews, appears to survive constitutional challenge once the strong medicine of NTEU is found to apply.”).

Harman v. City of New York, 140 F.3d 111, 115 (2d Cir. 1998).

Moonin v. Tice, 868 F. 3d 853, 867-68 (9th Cir. 2017).

See Christopher J. Diehl, Open Meetings and Closed Mouths: Elected Officials’ Free Speech Rights After Garcetti v. Ceballos, 61 Case W. Res. L. Rev. 551, 570 (2010) (“The Supreme Court has yet to address the free speech rights of elected officials in the wake of Garcetti – and it has never squarely addressed the extent of their free speech protection when they are performing their official duties.”).

Wood v. Georgia, 370 U.S. 375, 382-83 (1962).

Id. at 393.

Bond v. Floyd, 385 U.S. 116 (1966).

Id. at 127.

Id. at 135.

See, e.g., Greenman v. City of Hackensack, 486 F.Supp.3d 811, 825 (D.N.J. 2020) (concluding that Garcetti public-employee standard “simply doesn’t fit” in context of First Amendment retaliation claim by elected city council member, and opining that “[an] elected official enjoys the same First Amendment freedoms as any citizen”); Melville v. Town of Adams, 9 F.Supp.3d 77, 102 (D. Mass. 2014) (stating that “as distinct from the speech of public employees, Garcetti does not apply to elected officials’ speech, at least to the extent it concerns official duties”) (emphasis in original); Frenchko v. Monroe, No. 4:23-cv-781, 2023 WL 9249834 (N.D. Ohio Jan. 16, 2023) at *16-19 (finding in favor of elected county commissioner who alleged retaliatory arrest for speech at public meeting addressing matters of public concern, citing Supreme Court’s Wood and without mentioning Garcetti or other employee-speech caselaw); Bradshaw v. Salvaggio, SA-20-CV-01168, 2020 WL 8673836 (Oct. 28, 2020) at *24-25, adopted by Bradshaw v. Salvaggio, 2020 WL 8673835 (W.D. Tex. Oct. 30, 2020) (declining to apply Garcetti standard to First Amendment retaliation claim by city council member who accused colleagues of conspiring to oust him because of his criticism of police, and concluding that plaintiff “enjoys the same First Amendment protections as a City Councilor as he would as a public citizen”); Nordstrom v. Town of Stettin, No. 16-cv-616, 2017 WL 2116718 (W.D. Wis. May 15, 2017) at *4 (ruling in favor of town council member who alleged he was forced to resign in retaliation for his political speech, and observing that “[t]he reasoning of Bond counsels against extending Garcetti to elected officials’ speech, because doing so would contravene the manifest function of the First Amendment.”) (internal quotes omitted). But see Hogan v. Twp. of Haddon, Civil No. 04-2036, 2006 U.S. Dist. LEXIS 87200 (D.N.J. Dec. 1, 2006) at *18 (applying Garcetti to First Amendment claims of elected township commissioner and concluding that “as a public employee making statements pursuant to her official duties, [the plaintiff] has no personal First Amendment rights”); Shields v. Charter Twp. of Comstock, 617 F.Supp.2d 606, 615 (W.D. Mich. 2009) (citing Hogan and observing, in First Amendment case brought by former town council member who alleged colleagues silenced him, that as an elected council member, the plaintiff “may not technically have been an employee of the Township, but he surely was a representative of the Township, and the concerns underlying Garcetti apply with equal force to his situation”).

Velez v. Levy, 401 F.3d 75 (2d Cir. 2005).

Id. at 97.

Id.

Jenevein v. Willing, 493 F.3d 551, 557 (5th Cir. 2007). See also Boquist v. Courtney, 32 F.4th 764, 779 (9th Cir. 2022) (“The rationale for allowing the government to restrict the speech of government employees and contractors is not applicable to elected officials. … An elected official’s speech does not interfere with his performance of duties; to the contrary, the speech is a vital component of his duties(.)”). In Werkheiser v. Pocono Twp., the Third Circuit likewise expressed doubt that, when an elected official brings a First Amendment retaliation claim, Garcetti supplies the governing standard, writing: “Many of the reasons for restrictions on employee speech appear to apply with much less force in the context of elected officials. ... To use Garcetti’s language, his speech is neither ‘controlled’ nor ‘created’ in the same way that an employer controls the speech of a typical public employee.” 780 F.3d 172, 178 (3d Cir. 2015). But the court resolved Werkheiser on narrower qualified immunity grounds, noting the state of confusion in the law surrounding the constitutional status of elected-official speakers, without making a conclusive holding on the substantive First Amendment issue. Id. at 183.

Warren v. DeSantis, 90 F.4th 1115 (11th Cir. 2024).

Id. at 1134, 1139.

Id. at 1133.

Id. at 1130, 1134.

Shannon M. Wright, Censure As Speech? Houston Community College System v. Wilson and the Government Speech Doctrine, 59 Hous. L. Rev. 229, 252 (2021).

Wilson v. Hous. Cmty. Coll. Sys., 955 F. 3d 490, 493-94 (5th Cir. 2020).

Id. at 493.

Id. at 494.

Wilson v. Hous. Cmty. Coll. Sys., Civil Action No. 4:18-CV-00744, Memorandum Opinion and Order (S.D. Tex Mar. 22, 2019) (unpubl’d).

Wilson, 955 F. 3d at 497-98.

Houston Cmty. Coll. Sys. v. Wilson, 595 U.S. 468 (2022).

Id. at 475-76.

Id. at 478.

Id.

See Philip M. Napoli, What If More Speech Is No Longer the Solution: First Amendment Theory Meets Fake News and The Filter Bubble, 70 Fed. Comm. L.J. 55, 58 (2018) (“A central tenet of the First Amendment is that more speech is an effective remedy against the dissemination and consumption of false speech. … [T]he effectiveness of counterspeech has become an integral component of most conceptualizations of an effectively functioning ‘marketplace of ideas,’ in which direct government regulation of speech is minimized in favor of an open and competitive speech environment.”).

See Wilson, 595 U.S. at 478; see also infra note 82 and accompanying text.

564 U.S. 117 (2011).

Id. at 119-20.

Id. at 125-26.

Id. at 127.

Wilson, 595 U.S. at 482.

Rutan v. Republican Party of Ill., 497 U.S. 62, 75 n.8 (1990).

See, e.g., Rossy v. City of Bishop, 2019 WL 859583 at *5-6 (citing Rutan and finding that threat of disciplinary action, even if not carried out, could be sufficiently speech-chilling to violate employees’ First Amendment rights).

Coszalter v. City of Salem, 320 F. 3d 968, 974-75 (9th Cir. 2003).

Thomas W. Hodgkinson, Film’s Most Unforgettable Scene, Spectator (Mar. 12, 2022), https://www.spectator.co.uk/article/film-s-most-unforgettable-scene/.

See Rosalie Berger Levinson, Superimposing Title VII's Adverse Action Requirement on First Amendment Retaliation Claims: A Chilling Prospect for Government Employee Speech, 79 Tul. L. Rev. 669, 674 (2005) (noting caselaw from the Second, Fifth, Eighth and Eleventh circuits).

Lybrook v. Members of Farmington Mun. Sch. Bd. of Educ., 232 F3d 1334, 1340 (10th Cir. 2000). See also Colson v. Grohman, 174 F.3d 498, 512 (5th Cir. 1999) (finding no actionable adverse action, where former city council member alleged that faced criticism, false accusations, and an attempt to instigate an unfounded criminal investigation, in retaliation for her speech).

Power v. Summers, 226 F. 3d 815, 820 (7th Cir. 2000).

Id.

Blair v. Bethel Sch. Dist., 608 F. 3d 540 (9th Cir. 2010).

Id. at 544.

Id. at 544-45.

34 F. 3d 359, 363-64 (6th Cir. 1994). However, the court did find an actionable First Amendment retaliation claim based on more severe allegations that fellow council members threatened the plaintiff’s safety and his wife’s. Id. at 364-65.

235 F.3d 1243, 1248 (10th Cir. 2000)

See, e.g., Hensley v. City of Port Hueneme, No. 2:17-cv-08422, 2019 WL 3035057 (C.D. Cal. May 7, 2019) at *3-4 (citing Blair and finding no First Amendment claim over city council’s vote to reprimand him for remarks deemed improper, because reprimand was mere political statement and not tangible deprivation of benefits of office); Montgomery v. Hugine, No. 5:17-cv-1934, 2019 WL 2601545 (N.D. Ala. June 25, 2019) at *11 (concluding that college trustee failed to state actionable retaliation claim based on board’s censure resolution, because resolution did not affect trustee’s ability to vote, speak at meetings, or otherwise exercise his authority); Munoz-Feliciano v. Monroe-Woodbury Cent. Sch. Dist., No. 13-CV-4340, 2015 WL 1379702 (S.D.N.Y. Mar. 25, 2015) at *10 (finding no basis for First Amendment claim by school board candidate who was subjected to retaliatory “smear campaign” by other school district officials: “Hostile and accusatory comments are a common part of the electoral process in this country. This type of routine campaign speech must escape the reach of a viable First Amendment retaliation claim.”); Dillaplain v. Xenia Cmty. Sch. Bd. of Educ., No. 3:13-cv-104, 2013 WL 5724512 (S.D. Ohio Oct. 21, 2013) at *5 (citing Blair and declining to entertain school board member’s retaliation claim based on board’s enactment of censure resolution, which “may, itself, be protected speech under the First Amendment”); Westfall v. City of Crescent City, No. CV 10-5222, 2011 WL 4024663 (N.D. Cal. Sept. 9, 2011) at *3-4 (citing Blair, Zilich and Phelan, and ruling that, “in the political arena,” a censure resolution is not grounds for a First Amendment retaliation suit as long as the censured official retains the ability to participate in meetings, vote, and otherwise exercise the duties of office).

Boquist v. Courtney, 32 F.4th 764 (9th Cir. 2022).

Id. at 772-73.

Id. at 776-77.

Id. at 776.

Wilson Criscione, Will Any Candidate Change the Gag Rule Preventing Most Spokane School Board Members From Speaking to the Media? The Inlander (Oct. 28, 2019), https://www.inlander.com/news/will-any-candidate-change-the-gag-rule-preventing-most-spokane-school-board-members-from-speaking-to-the-media-18475664.

Id.

Id.

See Lee Juillerat, Surprise Valley Hospital Faces Financial Challenges, Herald & News (May 22, 2016) https://www.heraldandnews.com/news/local_news/surprise-valley-hospital-faces-financial-challenges/article_de6e0c78-c098-5e94-8e67-ec762b8923b2.html (stating that board members of public hospital district are bound by “one board” rule, which provides that members “will support the legitimacy and authority of the final determination of the board on any matter, irrespective of the member's personal position on the issue” and forbids publicly discussing board matters “except to repeat explicitly stated board decisions”); Walton County, Ga., Code of Ordinances, § 1.14, Code of Ethics and Conduct for Elected and Appointed Officials (providing that “first duties” require board members to “[s]peak with one voice once a majority decision has been rendered”); City of Bryan, Tex., Code of Ethics and Conduct for Elected and Appointed Officials, Ex. A, https://docs.bryantx.gov/council/ethics-code-2013.pdf (stating that “first duties” of city officials include duty to “speak with one voice once a majority decision has been rendered”). See also State Teachers Retirement Sys. of Ohio, Board Policies (Nov. 17, 2023), https://www.strsoh.org/_pdfs/board/board-policies.pdf, at 8 (stating that members of state board overseeing teacher pension system will “[e]ncourage and respect diversity of opinions during deliberations, but speak with one voice once decisions are made”).

See Garden City (Ks.) Cmty. College, Board of Trustees Handbook 2022-2023, https://www.gcccks.edu/about_gccc/board_of_trustee_documents/policy_docs/board_of_trustee_handbook.pdf at 27 (stating that college trustees should not “criticize or work