Abstract

Online comment sections, like those on news sites or social media, have the potential to foster informal public deliberation. Yet this potential is often undermined by the frequency of toxic or low-quality exchanges that occur in these settings. To combat this problem, platforms are increasingly leveraging algorithmic ranking to facilitate higher-quality discussions, e.g., by using civility classifiers or forms of prosocial ranking. However, these interventions may also inadvertently reduce the visibility of legitimate viewpoints, undermining another key aspect of deliberation: representation of diverse views. We seek to remedy this problem by introducing guarantees of representation into these methods. In particular, we adopt the notion of justified representation (JR) from the social choice literature and incorporate a JR constraint into the comment ranking setting. We find that enforcing JR leads to greater inclusion of diverse viewpoints while still being compatible with optimizing for user engagement or other measures of conversational quality.

1. Introduction

In theories of deliberative democracy [Habermas, 1991; Cohen, 2005; Fishkin, 2009; Bächtiger et al., 2018; Landemore, 2020], the legitimacy of collective decisions is grounded in the thoughtful and inclusive public deliberation that produces them. Deliberation that occurs in formal environments (e.g., a parliamentary meeting or citizens’ assembly) can be contrasted to the widespread and informal “deliberation in the wild” that happens in the public sphere (e.g., in coffee shops) [Habermas, 1991, 2023]. While the formal environments can be designed to provide ideal conditions for constructive deliberation, they do not easily scale—most people will not have the opportunity to regularly participate in citizens’ assemblies or parliamentary meetings. Therefore, improving informal public sphere deliberation may be essential for improving deliberation overall [Lazar and Manuali, 2024; Landemore, 2024].

Online platforms, like comment sections on news sites or social media, present an opportunity to expand public sphere deliberation [Helberger, 2019]. These digital spaces enable interactions between individuals who might never meet in person, potentially exposing them to a broader array of viewpoints. However, in reality, these online discussions often deteriorate into low-quality or toxic exchanges [Nelson et al., 2021; Kim et al., 2021]. In this work, we aim to leverage algorithmic tools to bring online conversations closer towards the ideals of deliberation. To clarify, we do not expect that online comment sections will achieve deliberative ideals to the same extent that in-person formal environments like citizens’ assemblies do. Nevertheless, we believe that striving towards deliberative ideals can be a valuable guiding principle for improving algorithmic interventions for these spaces.

What are the ideals that make a good deliberation? Deliberative democracy ideals generally demand at minimum (i) certain aspects of conversational quality (e.g., respect, reasoned arguments, etc.), and (ii) the representation of diverse voices. For example, Fishkin and Luskin [2005] claim that deliberative discussion must be (i) conscientious, i.e., “the participants should be willing to talk and listen, with civility and respect,” and (ii) comprehensive, i.e., “all points of view held by significant portions of the population should receive attention.” Similarly, in their review of the ‘second generation of deliberative ideals,’ Bächtiger et al. [2018] highlight the ongoing importance of (i) respect, and (ii) the evolving view of equality as the equality of opportunity to political influence [Knight and Johnson, 1997], which requires that people with diverse viewpoints be able to receive attention to their perspectives.

Algorithmic moderation and ranking have become key tools for facilitating conversational quality in online discussions [Kolhatkar et al., 2020]. For example, Google Jigsaw’s Perspective API comment classifiers have been used by prominent news organizations, such as The New York Times and The Wall Street Journal, to filter or rerank comments to improve civility]. More recently, a line of work on bridging-based ranking (BBR) has advocated for ranking aimed at bridging different perspectives and reducing polarization [Ovadya and Thorburn, 2023]. Most commonly, BBR is operationalized through ranking with diverse approval, which measures the extent to which a piece of content (e.g., a comment) receives approval across diverse groups of users. Diverse approval has been used in several high-impact applications like selecting crowd-sourced fact-checks on social media platforms [Wojcik et al., 2022] and selecting comments in collective response systems like Pol.is and Remesh [Small et al., 2021; Konya et al., 2023; Huang et al., 2024].

While these BBR interventions may improve conversational quality, the goal of ensuring representation in online discussions is less studied. In fact, solely focusing on conversational quality might inadvertently suppress the views of certain groups whose comments may be filtered out or may not appear high enough in the comment ranking to gain visibility. For example, civility classifiers have been shown to disproportionately flag as less “civil” comments written in African American English [Sap et al., 2019] and comments discussing encounters with racism [Lee et al., 2024]. In the context of diverse approval, the groups being bridged have a large effect on what content gets shown. Commonly, these groups correspond to political groups like left- or right-leaning users [Wojcik et al., 2022]. Therefore, it is plausible that diverse approval could give more visibility to politically moderate comments while failing to provide representation of others who hold more ideologically diverse views.

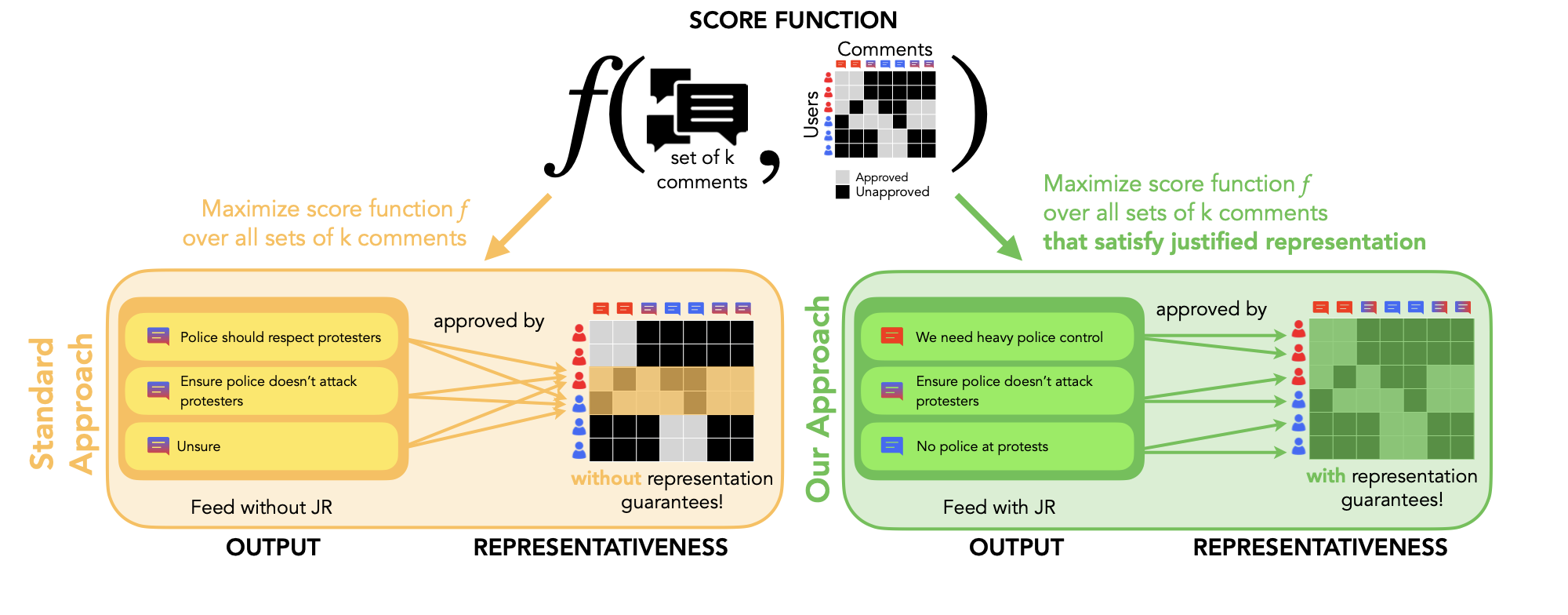

Incorporating representation constraints into comment ranking. In this blog post, we focus on sharing the results of our recent paper, “Representative Ranking for Deliberation in the Public Sphere” to a general audience. Our goal in this work was to broaden the scope of deliberative ideals examined in the algorithmic facilitation of online discussions [Revel et al., 2025]. In particular, we extended the existing focus on conversational quality to also include ideals of representation. In the typical approach, platforms rank comments based on some score function f which could encode conversational quality measures, as well as other measures relevant to the platform, such as user engagement. Platforms typically optimize such a score function without any guarantees on representation of diverse views.

We introduce such guarantees of representation into comment ranking methods. In particular, in our framework, the platform focuses on selecting a set of k comments to highlight (e.g., the top k comments in the ranking). By focusing on selecting a set of comments, we can begin to leverage notions of proportional representation. For example, we would not want all k comments to continuously represent the views of certain individuals while leaving other legitimate viewpoints unrepresented. To formalize this idea, we leverage a representation constraint from the social choice literature known as justified representation (JR), which requires outcomes to meet certain criteria related to proportionality. The platform’s overall goal is then to select the set of k comments that maximizes the score function (engagement, civility, etc.) while satisfying justified representation.

Figure 1: Our approach compared to the standard approach to ranking comments. In this example, a platform with six users wants to select three comments to highlight while optimizing a given score function f (e.g., engagement, civility, diverse approval, etc). This example is inspired by our experiments ranking comments related to campus protests in Section 3. In the standard approach, the platform simply selects the three comments with the highest score (in this case, diverse approval across the red and blue users). However, this leads to only two users having a comment that they approve of in the set selected— leaving two thirds of the users unrepresented in the feed without JR. On the other hand, in our approach, the platform picks the three comments that maximize the diverse approval score while satisfying JR—representing, in this case, all the users in the output feed with JR.

We conduct experiments implementing a JR constraint for ranking comments related to campus protests on Remesh. Remesh is a popular collective response system [Ovadya, 2023] that is used frequently by governments, non-profits, and corporations to elicit collective opinions at scale. We found that enforcing JR significantly enhanced representation without compromising other measures (engagement, diverse approval, or attributes like “nuance,” “reasoning,” “respect,” etc. [Saltz et al., 2024; Jigsaw]). Without JR, an average of 14 percent of participants (and up to 28 percent for certain posts) did not have any comments they approved of in the top comments, compared to only 4 percent (and up to 9 percent) with the JR constraint.

Our full paper contains the technical details as well as mathematical proofs [Revel et al., 2025]. In this essay, we focus on delving into the intuition behind this representation constraint and its advantages for this setting (Section 2), highlighting our experimental results on Remesh (Section 3), and discussing broader implications for algorithmic ranking and deliberative democracy (Section 4).

2. Incorporating Representation into Comment Ranking

Current algorithmic interventions in online discussions primarily emphasize conversation quality. We enhance these interventions by also addressing the representation of diverse viewpoints. To do so, we leverage a notion of representation from the social choice literature known as justified representation. In this section, we explain what justified representation entails, how we apply it alongside other conversational quality metrics in the comment ranking context, and how it differs from demographic-based representation.

2.1. What is justified representation?

Justified representation (JR) [Aziz et al., 2017] is a notion of representation from social choice theory, a field that studies mechanisms and voting rules for aggregating individual preferences into collective choices [Brandt et al., 2016]. JR, in particular, is a criterion for fair representation in multi-winner elections, where a group of individuals is selected to form a committee. In this setting, it is intuitive that different committee members should represent a diverse range of voters. Consider the following example that illustrates how outcomes can be unfair when this diversity is absent.

Example 1 (Unrepresentative Outcome). Imagine a scenario where 100 voters are electing a committee of 5 members. Suppose all 5 elected members are approved by the same 60 voters, while the remaining 40 voters do not have any elected member they approve of. The outcome arguably lacks fairness, as the same group of voters consistently receives representation, while the remaining voters are left unrepresented.

JR is a fairness criterion that rules out this type of unrepresentative outcome. At a high level, what JR requires is that any large enough group of voters with shared preferences receives at least one representative in the committee. This approach effectively ‘spreads out’ voter representation across the committee members, thereby avoiding outcomes like in Example 1.

Technically, what JR requires is that if there are n voters who are selecting a committee with k representatives, then for any group of n/k voters (large enough to deserve representation by proportionality) who all approve of at least one candidate in common (have some minimal cohesion in their preferences), at least one voter in the group must approve of at least one elected representative. There are also extensions of JR such as EJR [Aziz et al., 2017], PJR [Sánchez-Fernández et al., 2017], BJR [Fish et al., 2024], and EJR+ [Brill and Peters, 2023] that aim to provide more stringent guarantees of representation. In this work, we focus on understanding the price of imposing even the weaker criterion of JR for general scoring functions, but it would be interesting to explore extensions of JR in future work.

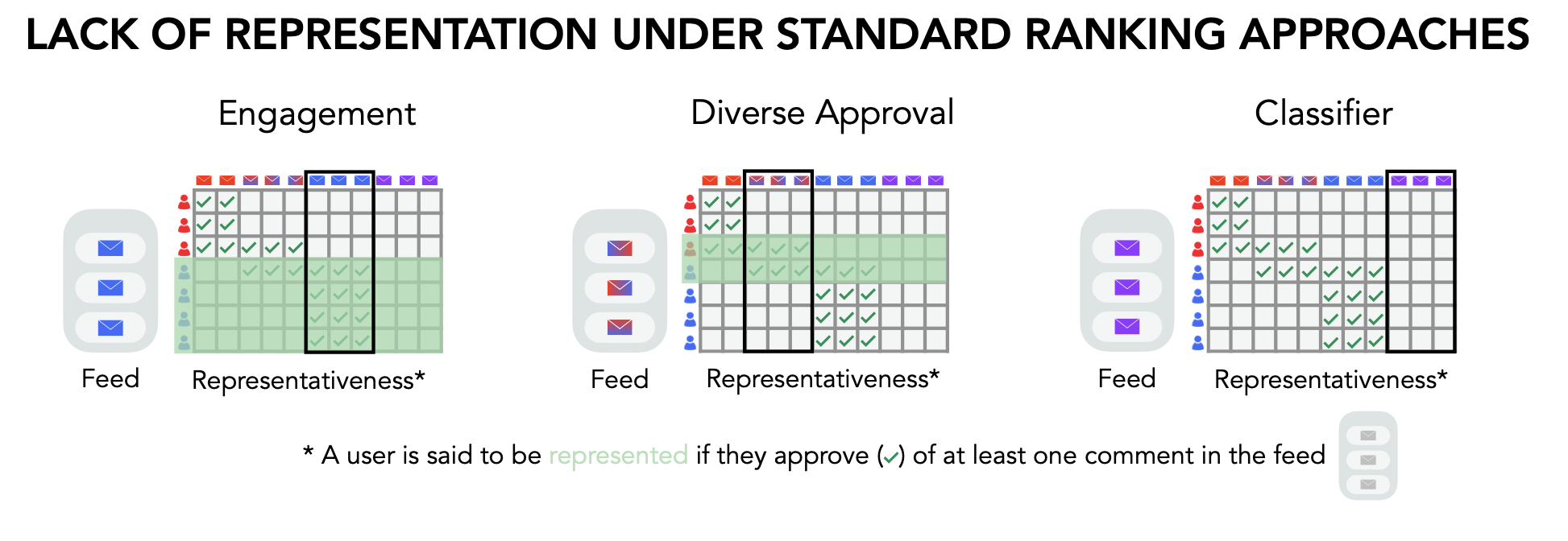

Figure 2: Example of common ranking methods failing to represent users’ viewpoints. The matrix displays the set of users and comments, where a green tick indicates that a user approved (or, was inferred to approve) a comment. We show three ways of ranking comments—by engagement, diverse approval, and a content-based classifier—and how they may result in unrepresentative outcomes. Under engagement, the comments with most overall approval (e.g., total upvotes) get selected. However, this results in the red users (the minority group in this case) having no comment they approve of. Under diverse approval [Ovadya and Thorburn, 2023], the comments that are approved by both blue and red users are picked, resulting in five users being unrepresented by the selected comments. Finally, with a content-based classifier, the comments with the highest score can be arbitrary and untied to users’ approval of comments. Here, we show a worst-case scenario where no user ends up being represented in the output feed.

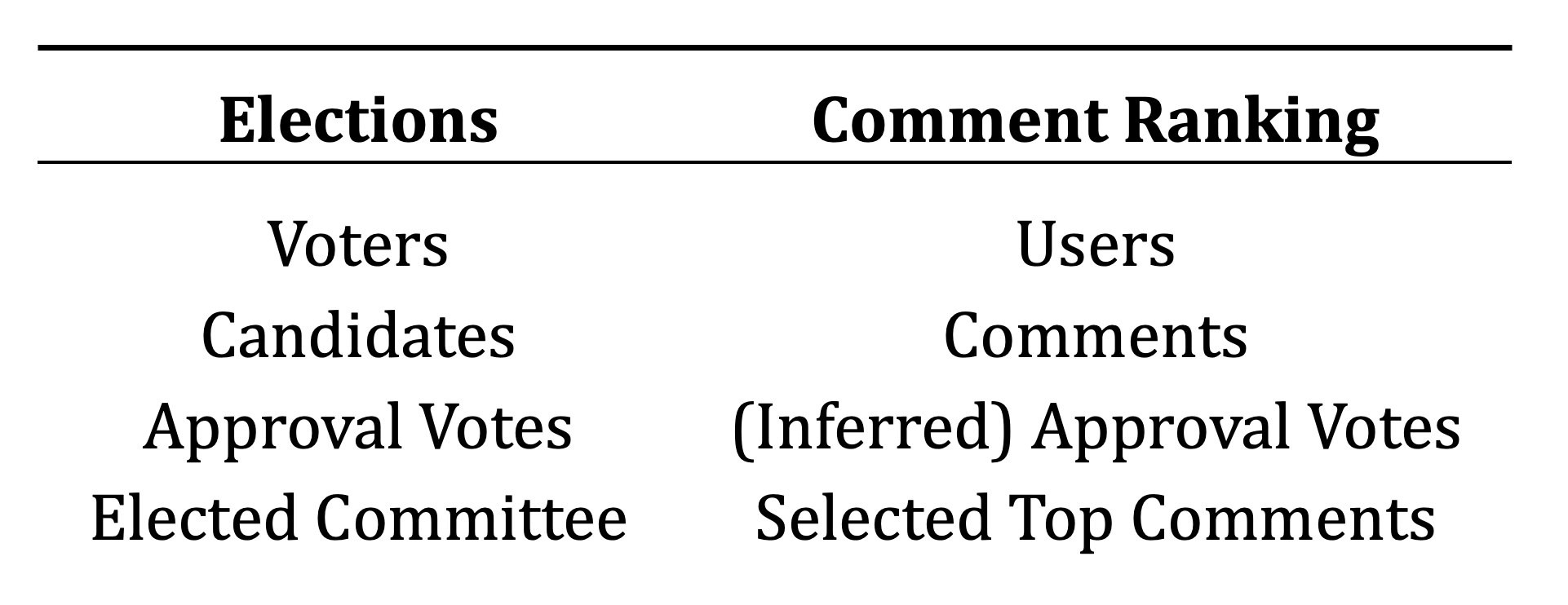

Table 1: Parallels between the election and comment ranking setting when applying JR. In the comment ranking setting, users are the ‘voters’ and comments become the ‘candidates’ that are being elected. However, users may not explicitly vote on all comments [Halpern et al., 2023], and thus, their approval of different comments must be inferred by their interactions on the platform (e.g., which comments they upvote or like).

2.2. Justified representation for comment ranking

In today’s digital landscape, online comment sections on social media and news sites have become popular venues for informal ‘public sphere’ deliberation. Algorithmic facilitation is increasingly employed to curate these online spaces. We propose that deliberative ideals can serve as a guiding principle for algorithmic interventions in these environments. While we do not expect online spaces to achieve these ideals to the same extent as curated in-person formal deliberations, we believe that striving towards these deliberative ideals can aid in designing effective algorithmic interventions for these platforms.

Thus far, algorithmic facilitation for comment ranking has primarily focused on enhancing the style and quality of conversation, e.g., by using classifiers that measure whether a comment is respectful or includes reasoning [Saltz et al., 2024]. However, these interventions overlook another key deliberative ideal: representation of diverse voices. In Figure 2, we show an example of how three common methods for ranking comments (by engagement, diverse approval, and content-based classifiers) may inadvertently result in the suppression of certain groups’ viewpoints, in the sense that no comments they approve of are in the top set of comments.

To remedy this, we suggest using justified representation as a criterion for representation in the comment ranking setting. Table 1 summarizes the parallels between the elections setting and the comment ranking setting when applying JR. In comment ranking, we can think of the comments as being ‘candidates’ while users on the platform are the ‘voters.’ A user may not vote on all possible comments, however, their approval of different comments can be inferred by their interactions, e.g., which comments they upvote or like. Since the top comments receive the most attention, deliberative ideals entail that they are chosen to fairly represent different opinions of users. Justified representation can serve as a useful criterion for fair representation in this context.

Our goal is to facilitate deliberative ideals broadly, so we formulate the use of JR in a way that is compatible with interventions aimed at other ideals. In particular, we select a set S of top comments by maximizing a score function f(S) (e.g., civility, bridging scores, etc.) while constraining the chosen set of comments S to satisfy justified representation. Our approach allows the score function to be arbitrarily chosen. This means our approach is compatible with any feature advancements in scoring functions for prosocial ranking—new score functions could simply be plugged into the framework. By focusing on the overall deliberative environment, our work differs from prior uses of JR and its extensions for online comments [Halpern et al., 2023; Fish et al., 2024] or for ranking in general [Skowron et al., 2017; Israel and Brill, 2024], which concentrated solely on representation. In all, by incorporating JR, we are able to construct feeds that combine conversational quality with guarantees of representation.

2.3. How does JR compare to demographic-based representation?

It is worth discussing how our JR-based approach to representation differs from other, perhaps more familiar, notions of demographic or social representation from the algorithmic fairness literature [Chasalow and Levy, 2021]. JR is a bottom-up measure where the groups that are represented depend entirely on the users’ own approval of different comments. This has several advantages in the comment ranking setting.

First is its feasibility for real-world applications. In algorithmic fairness, groups are typically pre-defined based on a demographic, such as race or religion. In contrast to JR, the requirement of (inference of) user demographic labels makes applying many algorithmic fairness methods infeasible or difficult to implement in industry settings, including on social media platforms, because of conflicts with privacy and legal constraints [Holstein et al., 2019; Veale and Binns, 2017]. We note that if a demographic is predictive of differences in viewpoints, then it is likely that enforcing JR can also improve demographic representation. For example, in our experiments ranking comments on Remesh in Section 3, we find that enforcing JR also increases representation across political groups.

Second, JR has the flexibility to automatically represent different groups for different settings. For example, the groups that are relevant to represent when ranking comments on an article about the 2025 New York City budget planning process are different from the groups that are relevant to represent on an article about a basketball game between the Celtics and Knicks. On a news site or social media platform where the relevant groups to represent for each post can be vastly different, it is difficult to scale up algorithmic fairness approaches that require pre-specifying the set of dimensions or demographics to consider.

Third, JR may accommodate intersectionality [Crenshaw, 1991] in a more natural way than many algorithmic fairness approaches. Algorithmic fairness approaches to intersectionality attempt to provide guarantees to a wide set of subgroups [Gohar and Cheng, 2023], e.g., by defining intersectional groups as the combination of different demographic attributes [Kearns et al., 2018]. However, this approach can lead to issues where the subgroups no longer correspond to meaningful entities. For instance, intersecting many dimensions can result in subgroups that are too specific and lack a meaningful reason for grouping (e.g., ‘Jewish white males aged 18-35 who have a bachelor’s degree and live in a rural area’). In contrast, JR focuses on cohesive groups—groups of users who can agree on at least one comment in common—thereby inherently embedding some requirement for meaningfulness.

Finally, our approach does not rule out consideration of demographics. In cases where representation across pre-defined groups is important, these groups can still be considered through the score function f. We have already given one example of score function, diverse approval, that may depend on pre-defined demographic groups.

3. Experiments Ranking Remesh Comments on Campus Protests

We turn to examining our approach in real-world settings, i.e., testing our approach on ranking comments from Remesh sessions on campus protests and the right to assemble. Remesh is a popularly used collective response system (CRS) [Ovadya, 2023]. Collective response systems are used by governments, companies, and non-profits to elicit the opinions of a target population at scale in a more participatory way than traditional polling. In particular, participants on a CRS give their opinion to different questions via free-form responses and then vote on whether they agree with other participants’ comments (as opposed to voting on a set of pre-specified options, as in traditional polling). In this way, a collective response system is more similar to the asynchronous dialogues that happen in comments sections on social media or online news platforms, where people post their thoughts in free-form text and can react to other people’s comments via likes, upvotes, downvotes, etc.

We experiment with ranking the Remesh comments using three types of scoring functions: engagement, diverse approval [Ovadya and Thorburn, 2023], and a score function based on Google Jigsaw’s Perspective API bridging classifiers [Saltz et al., 2024]. In Section 3.1 we detail our experimental set-up, and in Section 3.2 we discuss our results. Overall, our experiment shows that enforcing JR as a constraint can significantly improve the representation of diverse viewpoints without compromising other measures of conversational quality (i.e., engagement, diverse approval, and content-based measures of bridging).

3.1 Experimental setup

For these experiments, we use data from Remesh sessions conducted in the summer of 2024 in which a representative sample of Americans were asked about their opinions on campus protests and the right to assemble. Comments were generated through two separate sessions in which about 300 participants provided free-form answers to ten questions and voted on whether they agreed with others’ responses to these questions. We examine the impact of ranking the Remesh comments with and without a JR constraint for three kinds of scoring rules: engagement, diverse approval, and a bridging score based on Perspective API classifiers.

Engagement. The engagement scoring rule scores each comment based on the total number of people who approve it. It captures the overall popularity of each statement. This would be similar to ranking comments by the number of upvotes each comment received on a social media platform.

Diverse Approval. Diverse approval is the most common way to operationalize “bridging-based ranking,” ranking aimed at increasing mutual understanding and trust across divides [Ovadya and Thorburn, 2023]. Under diverse approval, the score of a comment reflects the level of approval it receives across diverse groups of users. The groups in diverse approval need to be either pre-specified or learned from the data. In this case, we operationalize diverse approval as the approval a comment receives across the three political groups in the Remesh dataset (left-, center-, and right-leaning). Notably, Remesh itself uses diverse approval as part of its functionalities to find “common ground” in participants’ contributed comments [Konya et al., 2023].

Perspective API Bridging Score. The Perspective API classifiers [Lees et al., 2022] are a suite of models developed by Google Jigsaw that have been used by prominent news organizations like The New York Times and The Wall Street Journal, for algorithmic filtering and ranking of comments. Traditionally, Perspective API focused on classifying whether a comment was toxic or not. However, Jigsaw recently introduced a new set of classifiers that, interestingly, are meant to capture attributes of comments related to “bridging” [Saltz et al., 2024]. The attributes are “affinity,” “compassion,” “curiosity,” “nuance,” “personal story,” “reasoning,” and “respect” [Jigsaw]. For our experiments, we calculated an overall bridging score for each comment by averaging its Perspective API scores for these attributes.

For each question, we selected the top eight comments under each scoring rule, both with and without a JR constraint. We now detail our findings on the effects of enforcing JR in the next section.

3.2 Results

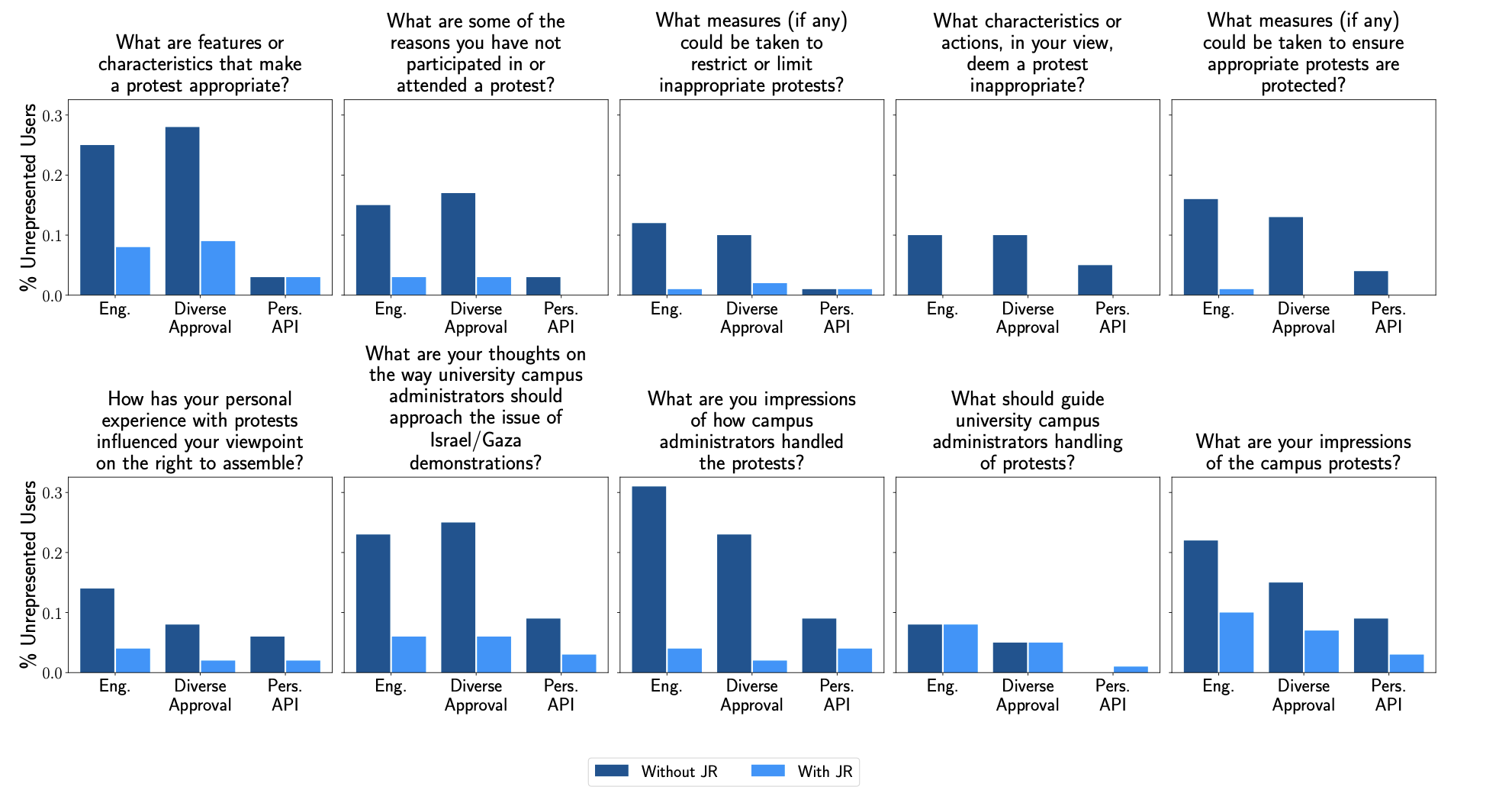

Figure 3 shows the results of ranking the Remesh comments using the three scoring functions (engagement, diverse approval, and Perspective API bridging score), both with and without a JR constraint. Below we highlight four key results: (1) enforcing JR leads to higher representation overall, (2) enforcing JR increases representation across political groups, (3) enforcing JR does not detract from measures of conversational quality, and (4) out of the three scoring functions, the Perspective API bridging score provided the greatest representation (both with and without JR constraint).

Enforcing JR leads to more users being represented. We say that a user is represented if they approve of at least one comment in the output feed. Figure 3 shows that the enforcement of JR leads to more users being represented. Without enforcing JR, 18 percent, 15 percent, and 4 percent of users were unrepresented in the engagement, diverse approval, or the Perspective API feeds respectively. After enforcing JR, these percentages decreased to five percent, four percent, and two percent. Note further that while we enforce JR, we find empirically that all but one of the JR sets selected satisfy a stronger notion of representation, EJR+ [Brill and Peters, 2023].

Figure 3: Representation when selecting eight Remesh comments, with and without a JR constraint. An individual who approves of at least one comment in a feed is said to be represented. This figure shows that the JR constraint significantly increases the number of individuals who are represented across feeds and across scoring rules.

Enforcing JR improves representation across political groups. As demonstrated in Appendix E.6 of our full paper, enforcing JR not only enhances overall representation but also improves representation for all three political groups (left, center, and right). This is notable because the JR criterion does not rely on any explicit ideological labels for users. Nonetheless, if political ideology correlates to differences in viewpoints, we may expect that JR would improve representation across political groups, which is indeed what we find.

Notably, JR improves representation across all three political groups even when ranking by diverse approval, which explicitly scores comments that receive approval across political groups more favorably. This could be because JR attempts to give representation to all large enough groups with common preferences, whereas diverse approval only focuses on the three specific political groups, making it possible that the content chosen by diverse approval always caters to the same participants in each of the three political groups, while leaving other subgroups unrepresented.

Enforcing JR is compatible with optimizing for engagement and other measures of conversational quality. One may wonder whether enforcing the JR constraint costs the platform with respect to its primary objective, whether measured through engagement, diverse approval, or the Perspective API. We can quantify the ‘price of JR’ as the difference between the optimal score achievable under a scoring function alone and the score achieved with the JR constraint. Interestingly, regardless of the scoring rule, the score of the feed satisfying JR is remarkably close to that of a feed that does not satisfy JR. Our results suggest that enforcing JR is compatible with optimizing for other measures of conversational quality or even user engagement. Details on the calculations for the ‘price of JR’ can be found in our full paper.

Ranking with the Perspective API bridging score resulted in more representation than ranking with engagement or diverse approval. Out of the three scoring functions we tested, the Perspective API bridging score provided the greatest representation. While we explicitly enforced JR using an approximation algorithm from social choice [Elkind et al., 2022], it is possible for a set chosen by one of the scoring functions to incidentally satisfy JR. Without explicit JR enforcement, the engagement, diverse approval, and Perspective API feeds satisfied JR 30 percent, 50 percent, and 100 percent of the time, respectively. Additionally, the number of users who approved of at least one comment in the selected set was consistently higher when using the Perspective API bridging score, both with and without explicit JR enforcement (see Figure 3).

The high level of representation achieved by the Perspective API bridging score is surprising, given that it is a content-based classifier that scores comments solely based on textual content. In theory, content-based classifiers might lead to poor representation outcomes, as they do not explicitly consider user approval when scoring comments (see Figure 2 for a worst-case scenario). Previous research has also shown that the classic Perspective API toxicity classifier has accuracy disparities across demographic groups [Sap et al., 2019; Ghosh et al., 2021; Garg et al., 2023], which might suggest that the Perspective API bridging classifiers would also offer lower representation.

Interestingly, the Perspective API bridging score provides better representation than diverse approval, which is the most common method for bridging-based ranking [Ovadya and Thorburn, 2023]. Our results suggest that the way the Perspective API bridging classifiers operationalize bridging may naturally lead to higher representation than diverse approval. This could be because the targeted bridging attributes (e.g., reason, nuance, and respect) appeal to a wide range of groups, whereas diverse approval typically focuses on bridging across a few predefined or learned groups.

4. Discussion

The online public sphere presents an opportunity to scale informal public deliberation. However, current tools for prosocial moderation and ranking online comments may also inadvertently suppress legitimate viewpoints, undermining another key aspect of deliberation: the inclusion of diverse viewpoints. In this paper, we introduced a general framework for algorithmic ranking that incorporates a representation constraint from social choice theory. We showed, in theory and practice, how enforcing this JR constraint can result in greater representation while being compatible with optimizing for other measures of conversational quality or even user engagement. Our work lays the groundwork for more principled algorithmic interventions that can uphold conversational norms while maintaining representation.

Limitations. In our work, we implemented a proof-of-concept that illustrates the benefits of incorporating representation constraints in the comment ranking setting. However, there are still additional questions that should be considered before deploying it on a real-world platform.

First, the JR representation constraint depends upon an approval matrix that specifies which users approve of which comments. However, it is not always clear which users should be included in the approval matrix. For example, should it be all users on the platform or only those who saw the post? The answer to this question will likely be different for different platforms.

Second, on real-world platforms, users will not ‘vote’ on all comments, and thus, their approval of various comments will need to be inferred [Halpern et al., 2023]. It is essential to ensure the accuracy of these inferences to provide users with genuine representation. (Our Remesh experiments in Section 3 also relied on inferences of the approval matrix and should be interpreted with this in mind.) Moreover, on many platforms, users’ approval will need to be inferred from engagement data such as upvotes or likes. If the chosen engagement significantly diverges from actual user approval, the validity of the process could be compromised. Investigating the impact of biased approval votes, in a similar vein as the work of Halpern et al. [2023] or Faliszewski et al. [2022], could be an interesting direction for future work.

Finally, it is crucial to test the effects of enforcing JR through A/B tests, as offline results may differ from those observed in real-world deployments. In our Remesh experiments, we found that enforcing JR came at little cost to other conversational quality measures and to user engagement. However, these were ‘offline experiments’ involving the re-ranking of historical data without deploying our new algorithm to users, and further testing is still needed.

AI and Democratic Freedoms. The symposium’s call for contributions invited us to delve into the impact of “AI-infused digital platforms” on democratic freedoms. Our research adopts a proactive stance, investigating how these technologies can be purposefully crafted to nurture the “preconditions for democracy.” This work is in fact part of a larger research initiative that examines how technology can be leveraged to promote democratic ideals [Summerfield et al., 2024]. Building upon initiatives like Remesh and Pol.is, which seek common ground through online asynchronous discussions, recent studies have explored the potential of large language models to transform individual comments into free-form statements with deliberative or representative qualities [Tessler et al., 2024; Fish et al., 2024; Revel and Pénigaud, 2025]. While this research trajectory enables the generation of new statements, allowing exploration of reasonable opinions beyond existing comments, our work introduces a complementary set of tools to ensure minimal representation within the traditional and still prevalent framework that mediates many of our interactions on digital platforms—online comment ranking.

References

Haris Aziz, Markus Brill, Vincent Conitzer, Edith Elkind, Rupert Freeman, and Toby Walsh. Justified Representation in Approval-Based Committee Voting. Social Choice and Welfare, 48(2):461–485, 2017.

André Bächtiger, John S Dryzek, Jane Mansbridge, and Mark E Warren. The Oxford Handbook of Deliberative Democracy, chapter Deliberative Democracy: an introduction. Oxford University Press, 2018.

Felix Brandt, Vincent Conitzer, Ulle Endriss, Jérôme Lang, and Ariel D. Procaccia. Handbook of Computational Social Choice. Cambridge University Press, USA, 1st edition, 2016. ISBN 1107060435.

Markus Brill and Jannik Peters. Robust and Verifiable Proportionality Axioms for Multiwinner Voting. In Proceedings of the 24th ACM Conference on Economics and Computation, EC ’23, page 301, New York, NY, USA, 2023. Association for Computing Machinery. ISBN 9798400701047. doi: 10.1145/3580507. 3597785. URL https://doi.org/10.1145/3580507.3597785.

Kyla Chasalow and Karen Levy. Representativeness in Statistics, Politics, and Machine Learning. In Proceedings of the 2021 ACM Conference on Fairness, Accountability, and Transparency, FAccT ’21, page 77–89, New York, NY, USA, 2021. Association for Computing Machinery. ISBN 9781450383097. doi: 10.1145/3442188.3445872. URL https://doi.org/10.1145/3442188.3445872.

Joshua Cohen. Deliberation and Democratic Legitimacy. In Debates in Contemporary Political Philosophy, pages 352–370. Routledge, 2005.

Kimberlé Crenshaw. Mapping the Margins: Intersectionality, Identity Politics, and Violence against Women of Color. Stanford Law Review, 43(6):1241–1299, 1991. ISSN 00389765. URL http://www.jstor.org/ stable/1229039.

Edith Elkind, Piotr Faliszewski, Ayumi Igarashi, Pasin Manurangsi, Ulrike Schmidt-Kraepelin, and Warut Suksompong. The Price of Justified Representation. In Proceedings of the AAAI Conference on Artificial Intelligence, pages 4983–4990, 2022.

Piotr Faliszewski, Grzegorz Gawron, and Bartosz Kusek. Robustness of Greedy Approval Rules. In European Conference on Multi-Agent Systems, pages 116–133. Springer, 2022.

Sara Fish, Paul Gölz, David C. Parkes, Ariel D. Procaccia, Gili Rusak, Itai Shapira, and Manuel Wüthrich. Generative Social Choice. In Proceedings of the 25th ACM Conference on Economics and Computation, EC ’24, page 985, New York, NY, USA, 2024. Association for Computing Machinery. ISBN 9798400707049. doi: 10.1145/3670865.3673547. URL https://doi.org/10.1145/3670865.3673547.

James S. Fishkin. When the People Speak: Deliberative Democracy and Public Consultation. Oxford Univesrity Press, 2009.

James S Fishkin and Robert C Luskin. Experimenting with a Democratic Ideal: Deliberative Polling and Public Opinion. Acta politica, 40:284–298, 2005.

Tanmay Garg, Sarah Masud, Tharun Suresh, and Tanmoy Chakraborty. Handling Bias in Toxic Speech Detection: A Survey. ACM Comput. Surv., 55(13s), July 2023. ISSN 0360-0300. doi: 10.1145/3580494.

URL https://doi.org/10.1145/3580494.

Sayan Ghosh, Dylan Baker, David Jurgens, and Vinodkumar Prabhakaran. Detecting Cross-geographic Biases in Toxicity Modeling on Social Media. In Wei Xu, Alan Ritter, Tim Baldwin, and Afshin Rahimi, editors, Proceedings of the Seventh Workshop on Noisy User-generated Text (W-NUT 2021), pages 313– 328, Online, November 2021. Association for Computational Linguistics. doi: 10.18653/v1/2021.wnut-1.35.

URL https://aclanthology.org/2021.wnut-1.35/.

Usman Gohar and Lu Cheng. A Survey on Intersectional Fairness in Machine Learning: Notions, Mitigation, and Challenges. In Proceedings of the Thirty-Second International Joint Conference on Artificial Intelligence, IJCAI ’23, 2023. ISBN 978-1-956792-03-4. doi: 10.24963/ijcai.2023/742. URL https://doi.org/10.24963/ijcai.2023/742.

Jürgen Habermas. The Structural Transformation of the Public Sphere: An Inquiry into a Category of Bourgeois Society. MIT press, 1991.

Jürgen Habermas. A new structural transformation of the public sphere and deliberative politics. John Wiley & Sons, 2023.

Daniel Halpern, Gregory Kehne, Ariel D Procaccia, Jamie Tucker-Foltz, and Manuel Wüthrich. Representation with Incomplete Votes. In Proceedings of the AAAI Conference on Artificial Intelligence, pages 5657–5664, 2023.

Natali Helberger. On the Democratic Role of News Recommenders. Digital Journalism, 7(8):993–1012, 2019. doi: 10.1080/21670811.2019.1623700. URL https://doi.org/10.1080/21670811.2019.1623700.

Kenneth Holstein, Jennifer Wortman Vaughan, Hal Daumé, Miro Dudik, and Hanna Wallach. Improving Fairness in Machine Learning Systems: What Do Industry Practitioners Need? In Proceedings of the 2019 CHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems, CHI ’19, page 1–16, New York, NY, USA, 2019. Association for Computing Machinery. ISBN 9781450359702. doi: 10.1145/3290605.3300830. URL https://doi.org/10.1145/3290605.3300830.

Saffron Huang, Divya Siddarth, Liane Lovitt, Thomas I. Liao, Esin Durmus, Alex Tamkin, and Deep Ganguli. Collective Constitutional AI: Aligning a Language Model with Public Input. In Proceedings of the 2024 ACM Conference on Fairness, Accountability, and Transparency, FAccT ’24, page 1395–1417, New York, NY, USA, 2024. Association for Computing Machinery. ISBN 9798400704505. doi: 10.1145/3630106. 3658979. URL https://doi.org/10.1145/3630106.3658979.

Jonas Israel and Markus Brill. Dynamic Proportional Rankings. Social Choice and Welfare, pages 1–41, 2024.

Jigsaw. Perspective API: Attributes & Languages. Url: https://developers.perspectiveapi.com/s/about-the-api-attributes-and-languages?language=en_US. Last accessed: June 4, 2025

Michael Kearns, Seth Neel, Aaron Roth, and Zhiwei Steven Wu. Preventing Fairness Gerrymandering: Auditing and Learning for Subgroup Fairness. In Jennifer Dy and Andreas Krause, editors, Proceedings of the 35th International Conference on Machine Learning, volume 80 of Proceedings of Machine Learning Research, pages 2564–2572. PMLR, 10–15 Jul 2018. URL https://proceedings.mlr.press/v80/ kearns18a.html.

Jin Woo Kim, Andrew Guess, Brendan Nyhan, and Jason Reifler. The Distorting Prism of Social Media: How Self-Selection and Exposure to Incivility Fuel Online Comment Toxicity. Journal of Communication, 71(6):922–946, 09 2021. ISSN 0021-9916. doi: 10.1093/joc/jqab034. URL https://doi.org/10.1093/ joc/jqab034.

Jack Knight and James Johnson. What Sort of Equality Does Deliberative Democracy Require? In Deliberative Democracy: Essays on Reason and Politics. The MIT Press, 11 1997. ISBN 9780262268936. doi: 10.7551/mitpress/2324.003.0013. URL https://doi.org/10.7551/mitpress/2324.003.0013.

Varada Kolhatkar, Nithum Thain, Jeffrey Sorensen, Lucas Dixon, and Maite Taboada. Classifying Constructive Comments, 2020. URL https://arxiv.org/abs/2004.05476.

Andrew Konya, Yeping Lina Qiu, Michael P Varga, and Aviv Ovadya. Elicitation inference optimization for multi-principal-agent alignment. In Workshop: Foundation Models for Decision Making, 2022.

Andrew Konya, Lisa Schirch, Colin Irwin, and Aviv Ovadya. Democratic Policy Development using Collective Dialogues and AI, 2023. URL https://arxiv.org/abs/2311.02242.

Matevž Kunaver and Tomaž Požrl. Diversity in Recommender Systems – A Survey. Knowledge-Based Systems, 123:154–162, 2017. ISSN 0950-7051. doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.knosys.2017.02.009. URL https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0950705117300680.

Hélène Landemore. Open Democracy: Reinventing Popular Rule for the Twenty-first Century. Princeton University Press, 2020.

Hélène Landemore. Can Artificial Intelligence Bring Deliberation to the Masses? In Conversations in Philosophy, Law, and Politics. Oxford University Press, 03 2024. ISBN 9780198864523. doi: 10.1093/oso/ 9780198864523.003.0003. URL https://doi.org/10.1093/oso/9780198864523.003.0003.

Seth Lazar and Lorenzo Manuali. Can LLMs Advance Democratic Values? arXiv preprint arXiv:2410.08418, 2024.

Cinoo Lee, Kristina Gligorić, Pratyusha Ria Kalluri, Maggie Harrington, Esin Durmus, Kiara L Sanchez, Nay San, Danny Tse, Xuan Zhao, MarYam G Hamedani, et al. People who share encounters with racism are silenced online by humans and machines, but a guideline-reframing intervention holds promise. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 121(38):e2322764121, 2024.

Alyssa Lees, Vinh Q. Tran, Yi Tay, Jeffrey Sorensen, Jai Gupta, Donald Metzler, and Lucy Vasserman. A New Generation of Perspective API: Efficient Multilingual Character-level Transformers. In Proceedings of the 28th ACM SIGKDD Conference on Knowledge Discovery and Data Mining, KDD ’22, page 3197–3207, New York, NY, USA, 2022. Association for Computing Machinery. ISBN 9781450393850. doi: 10.1145/ 3534678.3539147. URL https://doi.org/10.1145/3534678.3539147.

Maria N. Nelson, Thomas B. Ksiazek, and Nina Springer. Killing the Comments: Why Do News Organizations Remove User Commentary Functions? Journalism and Media, 2(4):572–583, 2021. ISSN 2673-5172. doi: 10.3390/journalmedia2040034. URL https://www.mdpi.com/2673-5172/2/4/34.

Aviv Ovadya. Generative CI through Collective Response Systems, 2023. URL https://arxiv.org/abs/ 2302.00672.

Aviv Ovadya and Luke Thorburn. Bridging Systems: Open Problems for Countering Destructive Divisiveness across Ranking, Recommenders, and Governance. Technical report, Knight First Amendment Institute, 10 2023. URL https://knightcolumbia.org/content/bridging-systems.

Manon Revel and Théophile Pénigaud. AI-Facilitated Collective Judgements. arXiv preprint arXiv:2503.05830, 2025.

Manon Revel, Smitha Milli, Tyler Lu, Jamelle Watson-Daniels, and Max Nickel. Representative Ranking for Deliberation in the Public Sphere. arXiv preprint arXiv:2503.18962, 2025.

Emily Saltz, Zaria Jalan, and Tin Acosta. Re-Ranking News Comments by Constructiveness and Curiosity Significantly Increases Perceived Respect, Trustworthiness, and Interest, 2024. URL https://arxiv.org/ abs/2404.05429.

Maarten Sap, Dallas Card, Saadia Gabriel, Yejin Choi, and Noah A. Smith. The Risk of Racial Bias in Hate Speech Detection. In Anna Korhonen, David Traum, and Lluís Màrquez, editors, Proceedings of the 57th Annual Meeting of the Association for Computational Linguistics, pages 1668–1678, Florence, Italy, July 2019. Association for Computational Linguistics. doi: 10.18653/v1/P19-1163. URL https://aclanthology.org/P19-1163/.

Piotr Skowron, Martin Lackner, Markus Brill, Dominik Peters, and Edith Elkind. Proportional Rankings. In Proceedings of the Twenty-Sixth International Joint Conference on Artificial Intelligence, IJCAI-17, pages 409–415, 2017. doi: 10.24963/ijcai.2017/58. URL https://doi.org/10.24963/ijcai.2017/58.

Christopher Small, Michael Bjorkegren, Timo Erkkilä, Lynette Shaw, and Colin Megill. Polis: Scaling Deliberation by Mapping High Dimensional Opinion Spaces. Recerca. Revista de Pensament i Ana`lisi, 26 (2):1–26, 2021. doi: 0.6035/recerca.5516.

Christopher Summerfield, Lisa Argyle, Michiel Bakker, Teddy Collins, Esin Durmus, Tyna Eloundou, Iason Gabriel, Deep Ganguli, Kobi Hackenburg, Gillian Hadfield, et al. How Will Advanced AI Systems Impact Democracy? arXiv preprint arXiv:2409.06729, 2024.

Luis Sánchez-Fernández, Edith Elkind, Martin Lackner, Norberto Fernández, Jesús Fisteus, Pablo Basanta Val, and Piotr Skowron. Proportional Justified Representation. Proceedings of the AAAI Conference on Artificial Intelligence, 31(1), Feb. 2017. doi: 10.1609/aaai.v31i1.10611. URL https://ojs.aaai.org/ index.php/AAAI/article/view/10611.

Michael Henry Tessler, Michiel A Bakker, Daniel Jarrett, Hannah Sheahan, Martin J Chadwick, Raphael Koster, Georgina Evans, Lucy Campbell-Gillingham, Tantum Collins, David C Parkes, et al. AI Can Help Humans Find Common Ground in Democratic Deliberation. Science, 386(6719):eadq2852, 2024.

Michael Veale and Reuben Binns. Fairer Machine Learning in the Real World: Mitigating Discrimination without Collecting Sensitive Data. Big Data & Society, 4(2):2053951717743530, 2017. doi: 10.1177/ 2053951717743530. URL https://doi.org/10.1177/2053951717743530.

Stefan Wojcik, Sophie Hilgard, Nick Judd, Delia Mocanu, Stephen Ragain, M. B. Fallin Hunzaker, Keith Coleman, and Jay Baxter. Birdwatch: Crowd Wisdom and Bridging Algorithms can Inform Understanding and Reduce the Spread of Misinformation, 2022. URL https://arxiv.org/abs/2210.15723.

Yuying Zhao, Yu Wang, Yunchao Liu, Xueqi Cheng, Charu C. Aggarwal, and Tyler Derr. Fairness and Diversity in Recommender Systems: A Survey. ACM Trans. Intell. Syst. Technol., 16(1), January 2025. ISSN 2157-6904. doi: 10.1145/3664928. URL https://doi.org/10.1145/3664928.

© 2025, Manon Revel, Smitha Milli, Tyler Lu, Jamelle Watson-Daniels, and Maximilian Nickel

Cite as: Manon Revel, Smitha Milli, Tyler Lu, Jamelle Watson-Daniels, and Maximilian Nickel, Representative Ranking for Deliberation in the Public Sphere, 25-12 Knight First Amend. Inst. (June 12, 2025), https://knightcolumbia.org/content/representative-ranking-for-deliberation-in-the-public-sphere [https://perma.cc/YJC2-A864].

See: “10 New Languages for Perspective API”, updated May 20, 2025,

https://medium.com/jigsaw/10-new-languages-for-perspective-api-8cb0ad599d7c

See also: Meta, “Community Notes: A New Way to Add Context to Posts,” updated April 7, 2025, https://transparency.meta.com/features/community-notes.

Or, imagine an online platform with Celtics (the Boston basketball team) and Knicks (the New York City basketball team) fans whereby the only posts that get cross attention are those about Kadeem Allen (a former player in both franchises). Bridging-based ranking à la Ovadya and Thorburn [2023] may overly represent the Kadeem Allen posts, downgrading legitimate interest of the broader fan-bases.

Work on diversity in recommender systems also focuses on sets of items, but with the goal of showing ‘diverse’ items where diversity is typically defined based on the content of the items, e.g., showing videos spanning different topics or genres [Kunaver and Požrl, 2017, Zhao et al., 2025]. In contrast, our focus is on selecting sets of items (comments) to ensure that the top items provide a degree of proportional representation to users.

The data are available at https://github.com/akonya/polarized-issues-data.

Since individuals only give feedback on a small set of comments, we use inferences of the full approval matrix. In particular, we take the probabilistic agreement inferences [Konya et al., 2022] conducted by Remesh (in which each user and comment are given a probability of that user agreeing with that comment), and threshold these inferences by 0.5 to get a binary approval matrix.

To enforce the JR constraint, we use a greedy algorithm [Elkind et al., 2022].

Knight First Amendment Institute, “Call for Abstracts: Artificial Intelligence and Democratic Freedoms,” August 15, 2024, https://knightcolumbia.org/blog/call-for-abstracts-artificial-intelligence-and-democratic-freedoms

Knight First Amendment Institute, “Call for Abstracts: Artificial Intelligence and Democratic Freedoms.”

Manon Revel is a postdoctoral AI researcher at Meta FAIR and a research affiliate at the Berkman Klein Center for Internet & Society at Harvard University.

Smitha Milli is a postdoctoral associate at Cornell Tech.

Tyler Lu is a research scientist at Meta.

Jamelle Watson-Daniels is a research scientist at Meta FAIR.

Maximilian Nickel is a research scientist at Meta FAIR.